- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author videos

- ESC Content Collections

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About European Heart Journal Supplements

- About the European Society of Cardiology

- ESC Publications

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, case presentation.

- < Previous

Clinical case: heart failure and ischaemic heart disease

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Giuseppe M C Rosano, Clinical case: heart failure and ischaemic heart disease, European Heart Journal Supplements , Volume 21, Issue Supplement_C, April 2019, Pages C42–C44, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/suz046

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Patients with ischaemic heart disease that develop heart failure should be treated as per appropriate European Society of Cardiology/Heart Failure Association (ESC/HFA) guidelines.

Glucose control in diabetic patients with heart failure should be more lenient that in patients without cardiovascular disease.

Optimization of cardiac metabolism and control of heart rate should be a priority for the treatment of angina in patients with heart failure of ischaemic origin.

This clinical case refers to an 83-year-old man with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and shows that implementation of appropriate medical therapy according to the European Society of Cardiology/Heart Failure Association (ESC/HFA) guidelines improves symptoms and quality of life. 1 The case also illustrates that optimization of glucose metabolism with a more lenient glucose control was most probably important in improving the overall clinical status and functional capacity.

The patient has family history of coronary artery disease as his brother had suffered an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) at the age of 64 and his sister had received coronary artery by-pass. He also has a 14-year diagnosis of arterial hypertension, and he is diabetic on oral glucose-lowering agents since 12 years. He smokes 30 cigarettes per day since childhood.

In February 2009, after 2 weeks of angina for moderate efforts, he suffered an acute anterior myocardial infarction. He presented late (after 14 h since symptom onset) at the hospital where he had been treated conservatively and had been discharged on medical therapy: Atenolol 50 mg o.d., Amlodipine 2.5 mg o.d., Aspirin 100 mg o.d., Atorvastatin 20 mg o.d., Metformin 500 mg tds, Gliclazide 30 mg o.d., Salmeterol 50, and Fluticasone 500 mg oral inhalers.

Four weeks after discharge, he underwent a planned electrocardiogram (ECG) stress test that documented silent effort-induced ST-segment depression (1.5 mm in V4–V6) at 50 W.

He underwent a coronary angiography (June 2009) and left ventriculography that showed a not dilated left ventricle with apical dyskinesia, normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, 52%); occlusion of proximal LAD, 60% stenosis of circumflex (CX), and 60% stenosis of distal right coronary artery (RCA). An attempt to cross the occluded left anterior descending (LAD) was unsuccessful.

He was therefore discharged on medical therapy with: Atenolol 50 mg o.d., Atorvastatin 20 mg o.d., Amlodipine 2.5 mg o.d., Perindopril 4 mg o.d., oral isosorbide mono-nitrate (ISMN) 60 mg o.d., Aspirin 100 mg o.d., metformin 850 mg tds, Gliclazide 30 mg o.d., Salmeterol 50 mcg, and Fluticasone 500 mcg b.i.d. oral inhalers.

He had been well for a few months but in March 2010 he started to complain of retrosternal constriction associated to dyspnoea for moderate efforts (New York Heart Association (NYHA) II–III, Canadian Class II).

For this reason, he was prescribed a second coronary angiography that showed progression of atherosclerosis with 80% stenosis on the circumflex (after the I obtuse marginal branch) and distal RCA. The LAD was still occluded.

After consultation with the heart team, CABG was avoided because surgical the risk was deemed too high and the patient underwent palliative percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of CX and RCA. It was again attempted to cross the occlusion on the LAD. But this attempt was, again, unsuccessful. Collateral circulation from posterior interventricular artery (PDL) to the LAD was found. The pre-PCI echocardiogram documented moderate left ventricular dysfunction (EF 38%), the pre-discharge echocardiogram documented a LVEF of 34%. Because of the reduced LVEF, atenolol was changed for Bisoprolol (5 mg o.d.).

At follow-up visit in December 2012, the clinical status and the haemodynamic conditions had deteriorated. He complained of worsening effort-induced dyspnoea/angina that now occurred for less than a flight of stairs (NYHA III). On clinical examination clear signs of worsening heart failure were detected ( Table 1 ). His medical therapy was modified to: Bisoprolol 5 mg o.d., Atorvastatin 20 mg o.d., Amlodipine 2.5 mg o.d., Perindopil 5 mg o.d., ISMN 60 mg o.d., Aspirin 100 mg o.d., Metformin 500 mg tds, Furosemide 50 mg o.d., Gliclazide 30 mg o.d., Salmeterol 50 mcg oral inhaler, and Fluticasone 500 mcg oral inhaler. A stress perfusion cardiac scintigraphy was requested and revealed dilated ventricles with LVEF 19%, fixed apical perfusion defect and reversible perfusion defect of the antero-septal wall (ischaemic burden <10%, Figure 1 ). He was admitted, and an ICD was implanted.

Clinical parameters during follow-up visits

| . | December 2012 . | March 2013 . | September 2013 . | January 2014 . | January 2015 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 72 | 71 | 74 | 70 | 68 |

| Height (cm) | 170 | 170 | 170 | 170 | 170 |

| BMI | 24.9 | 24.9 | 25.1 | 24.9 | 24.8 |

| JVP | +2 cm H O | +2 cm H O | +2 cm H O | Normal | Normal |

| Oedema | Bilateral oedema up to mid shins | Bilateral pretibial oedema (2+) | Bilateral pretibial oedema (3+) | No pedal oedema | No pedal oedema |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | 115/80 | 115/75 | 110/60 | 110/70 | 112/68 |

| Pulse (bpm) | 88 | 86 | 92 | 68 | 56 |

| Auscultation | |||||

| Heart | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex, III sound | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex, III sound | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex, III sound | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex |

| Lungs | Bilateral fine basilar crackles | Bilateral fine basilar crackles | Bilateral fine basilar and mid lung crackles | Clear | Clear |

| Laboratory findings | |||||

| FPG (mg/dL) | 100 | 98 | 96 | 106 | 112 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.8 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 7 | 7.3 |

| Plasma creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

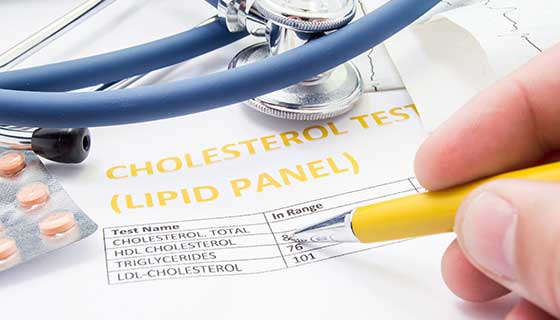

| Triglycerides | 118 mg/dL | NA | NA | 107 mg/dL | 114 mg/dL |

| Total cholesterol | 146 mg/dL | NA | NA | 142 mg/dL | 148 mg/dL |

| LDL-C | 68 mg/dL | NA | NA | 64 mg/dL | 68 mg/dL |

| HDL-C | 51 mg/dL | NA | NA | 48 mg/dL | 54 mg/dL |

| BNP | NA | 862 | 1670 | 276 | 244 |

| LVEF | 19 | 20 | 32 | 32 | |

| . | December 2012 . | March 2013 . | September 2013 . | January 2014 . | January 2015 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 72 | 71 | 74 | 70 | 68 |

| Height (cm) | 170 | 170 | 170 | 170 | 170 |

| BMI | 24.9 | 24.9 | 25.1 | 24.9 | 24.8 |

| JVP | +2 cm H O | +2 cm H O | +2 cm H O | Normal | Normal |

| Oedema | Bilateral oedema up to mid shins | Bilateral pretibial oedema (2+) | Bilateral pretibial oedema (3+) | No pedal oedema | No pedal oedema |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | 115/80 | 115/75 | 110/60 | 110/70 | 112/68 |

| Pulse (bpm) | 88 | 86 | 92 | 68 | 56 |

| Auscultation | |||||

| Heart | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex, III sound | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex, III sound | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex, III sound | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex |

| Lungs | Bilateral fine basilar crackles | Bilateral fine basilar crackles | Bilateral fine basilar and mid lung crackles | Clear | Clear |

| Laboratory findings | |||||

| FPG (mg/dL) | 100 | 98 | 96 | 106 | 112 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.8 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 7 | 7.3 |

| Plasma creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Triglycerides | 118 mg/dL | NA | NA | 107 mg/dL | 114 mg/dL |

| Total cholesterol | 146 mg/dL | NA | NA | 142 mg/dL | 148 mg/dL |

| LDL-C | 68 mg/dL | NA | NA | 64 mg/dL | 68 mg/dL |

| HDL-C | 51 mg/dL | NA | NA | 48 mg/dL | 54 mg/dL |

| BNP | NA | 862 | 1670 | 276 | 244 |

| LVEF | 19 | 20 | 32 | 32 | |

Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy and left ventriculography showing dilated left ventricle with left ventricular ejection fraction 19%. Reversible perfusion defects on the antero-septal wall and fixed apical perfusion defect.

In March 2013, he felt slightly better but still complained of effort-induced dyspnoea/angina (NYHA III, Table 1 ). Medical therapy was updated with bisoprolol changed with Nebivolol 5 mg o.d. and perindopril changed to Enalapril 10 mg b.i.d. The switch from bisoprolol to nebivolol was undertaken because of the better tolerability and outcome data with nebivolol in elderly patients with heart failure. Perindopril was switched to enalapril because the first one has no indication for the treatment of heart failure.

In September 2013, the clinical conditions were unchanged, he still complained of effort-induced dyspnoea/angina (NYHA III) and did not notice any change in his exercise capacity. His BNP was 1670. He was referred for a 3-month cycle of cardiac rehabilitation during which his medical therapy was changed to: Nebivolol 5 mg o.d., Ivabradine 5 mg b.i.d., uptitrated in October to 7.5 b.i.d., Trimetazidine 20 mg tds, Furosemide 50 mg, Metolazone 5 mg o.d., K-canrenoate 50 mg, Enalapril 10 mg b.i.d., Clopidogrel 75 mg o.d., Atorvastatin 40 mg o.d., Metformin 500 mg b.i.d., Salmeterol 50 mcg oral inhaler, and Fluticasone 500 mcg oral inhaler.

At the follow-up visit in January 2014, he felt much better and had symptomatically, he no longer complained of angina, nor dyspnoea (NYHA Class II, Table 1 ). Trimetazidine was added because of its benefits in heart failure patients of ischaemic origin and because of its effect on functional capacity. Ivabradine was added to reduce heart rate since it was felt that increasing nebivolol, that was already titrated to an effective dose, would have had led to hypotension.

He missed his follow-up visits in June and October 2014 because he was feeling well and he had decided to spend some time at his house in the south of Italy. In January and June 2015, he was well, asymptomatic (NYHA I–II) and able to attend his daily activities. He did not complain of angina nor dyspnoea and reported no limitations in his daily activities. Unfortunately, in November 2015 he was hit by a moped while on the zebra crossing in Rome and he later died in hospital as a consequence of the trauma.

This case highlights the need of optimizing both the heart failure and the anti-anginal medications in patients with heart failure of ischaemic origin. This patient has improved dramatically after the up-titration of diuretics, the control of heart rate with nebivolol and ivabradine and the additional use of trimetazidine. 1–3 All these drugs have contributed to improve the clinical status together with a more lenient control of glucose metabolism. 4 This is another crucial point to take into account in diabetic patients, especially if elderly, with heart failure in whom aggressive glucose control is detrimental for their functional capacity and long-term prognosis. 5

IRCCS San Raffaele - Ricerca corrente Ministero della Salute 2018.

Conflict of interest : none declared. The authors didn’t receive any financial support in terms of honorarium by Servier for the supplement articles.

Ponikowski P , Voors AA , Anker SD , Bueno H , Cleland JG , Coats AJ , Falk V , González-Juanatey JR , Harjola VP , Jankowska EA , Jessup M , Linde C , Nihoyannopoulos P , Parissis JT , Pieske B , Riley JP , Rosano GM , Ruilope LM , Ruschitzka F , Rutten FH , van der Meer P ; Authors/Task Force Members. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the Special Contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC . Eur J Heart Fail 2016 ; 18 : 891 – 975 .

Google Scholar

Rosano GM , Vitale C. Metabolic modulation of cardiac metabolism in heart failure . Card Fail Rev 2018 ; 4 : 99 – 103 .

Vitale C , Ilaria S , Rosano GM. Pharmacological interventions effective in improving exercise capacity in heart failure . Card Fail Rev 2018 ; 4 : 1 – 27 .

Seferović PM , Petrie MC , Filippatos GS , Anker SD , Rosano G , Bauersachs J , Paulus WJ , Komajda M , Cosentino F , de Boer RA , Farmakis D , Doehner W , Lambrinou E , Lopatin Y , Piepoli MF , Theodorakis MJ , Wiggers H , Lekakis J , Mebazaa A , Mamas MA , Tschöpe C , Hoes AW , Seferović JP , Logue J , McDonagh T , Riley JP , Milinković I , Polovina M , van Veldhuisen DJ , Lainscak M , Maggioni AP , Ruschitzka F , McMurray JJV. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and heart failure: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology . Eur J Heart Fail 2018 ; 20 : 853 – 872 .

Vitale C , Spoletini I , Rosano GM. Frailty in heart failure: implications for management . Card Fail Rev 2018 ; 4 : 104 – 106 .

- myocardial ischemia

- cardiac rehabilitation

- heart failure

- older adult

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| April 2019 | 719 |

| May 2019 | 146 |

| June 2019 | 86 |

| July 2019 | 98 |

| August 2019 | 112 |

| September 2019 | 144 |

| October 2019 | 281 |

| November 2019 | 263 |

| December 2019 | 229 |

| January 2020 | 254 |

| February 2020 | 303 |

| March 2020 | 271 |

| April 2020 | 380 |

| May 2020 | 372 |

| June 2020 | 427 |

| July 2020 | 320 |

| August 2020 | 307 |

| September 2020 | 376 |

| October 2020 | 553 |

| November 2020 | 459 |

| December 2020 | 473 |

| January 2021 | 305 |

| February 2021 | 424 |

| March 2021 | 479 |

| April 2021 | 445 |

| May 2021 | 251 |

| June 2021 | 307 |

| July 2021 | 228 |

| August 2021 | 248 |

| September 2021 | 383 |

| October 2021 | 414 |

| November 2021 | 442 |

| December 2021 | 367 |

| January 2022 | 276 |

| February 2022 | 354 |

| March 2022 | 537 |

| April 2022 | 373 |

| May 2022 | 451 |

| June 2022 | 253 |

| July 2022 | 161 |

| August 2022 | 208 |

| September 2022 | 281 |

| October 2022 | 424 |

| November 2022 | 568 |

| December 2022 | 442 |

| January 2023 | 305 |

| February 2023 | 357 |

| March 2023 | 533 |

| April 2023 | 474 |

| May 2023 | 403 |

| June 2023 | 235 |

| July 2023 | 242 |

| August 2023 | 230 |

| September 2023 | 339 |

| October 2023 | 456 |

| November 2023 | 477 |

| December 2023 | 262 |

| January 2024 | 226 |

| February 2024 | 283 |

| March 2024 | 282 |

| April 2024 | 400 |

| May 2024 | 298 |

| June 2024 | 103 |

| July 2024 | 119 |

| August 2024 | 125 |

| September 2024 | 82 |

Email alerts

More on this topic, related articles in pubmed, citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1554-2815

- Print ISSN 1520-765X

- Copyright © 2024 European Society of Cardiology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 5: 10 Real Cases on Acute Heart Failure Syndrome: Diagnosis, Management, and Follow-Up

Swathi Roy; Gayathri Kamalakkannan

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Case review, case discussion.

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Case 1: Diagnosis and Management of New-Onset Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction

A 54-year-old woman presented to the telemetry floor with shortness of breath (SOB) for 4 months that progressed to an extent that she was unable to perform daily activities. She also used 3 pillows to sleep and often woke up from sleep due to difficulty catching her breath. Her medical history included hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and history of triple bypass surgery 4 years ago. Her current home medications included aspirin, atorvastatin, amlodipine, and metformin. No significant social or family history was noted. Her vital signs were stable. Physical examination showed bilateral diffuse crackles in lungs, elevated jugular venous pressure, and 2+ pitting lower extremity edema. ECG showed normal sinus rhythm with left ventricular hypertrophy. Chest x-ray showed vascular congestion. Laboratory results showed a pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (pro-BNP) level of 874 pg/mL and troponin level of 0.22 ng/mL. Thyroid panel was normal. An echocardiogram demonstrated systolic dysfunction, mild mitral regurgitation, a dilated left atrium, and an ejection fraction (EF) of 33%. How would you manage this case?

In this case, a patient with known history of coronary artery disease presented with worsening of shortness of breath with lower extremity edema and jugular venous distension along with crackles in the lung. The sign and symptoms along with labs and imaging findings point to diagnosis of heart failure with reduced EF (HFrEF). She should be treated with diuretics and guideline-directed medical therapy for congestive heart failure (CHF). Telemetry monitoring for arrythmia should be performed, especially with structural heart disease. Electrolyte and urine output monitoring should be continued.

In the initial evaluation of patients who present with signs and symptoms of heart failure, pro-BNP level measurement may be used as both a diagnostic and prognostic tool. Based on left ventricular EF (LVEF), heart failure is classified into heart failure with preserved EF (HFpEF) if LVEF is >50%, HFrEF if LVEF is <40%, and heart failure with mid-range EF (HFmEF) if LVEF is 40% to 50%. All patients with symptomatic heart failure should be started on an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor (or angiotensin receptor blocker if ACE inhibitor is not tolerated) and β-blocker, as appropriate. In addition, in patients with New York Heart Association functional classes II through IV, an aldosterone antagonist should be prescribed. In African American patients, hydralazine and nitrates should be added. Recent recommendations also recommend starting an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) in patients who are symptomatic on ACE inhibitors.

Get Free Access Through Your Institution

Pop-up div successfully displayed.

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Eur Heart J Case Rep

- v.4(4); 2020 Aug

A case report of myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary artery disease: Graves’ disease-induced coronary artery vasospasm

Margo klomp.

y1 Department of Cardiology, Dijklander Hospital, Location Hoorn, Maelsonstraat 3, 1624 NP Hoorn, the Netherlands

Sarah E Siegelaar

y2 Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Amsterdam University Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Tim P van de Hoef

y3 Department of Cardiology, Amsterdam University Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Marcel A M Beijk

Associated data.

Coronary artery spasm can occur either in response to drugs or toxins. This response may result in hyper-reactivity of vascular smooth muscles or may occur spontaneously as a result of disorders in the coronary vasomotor tone. Hyperthyroidism is associated with coronary artery spasm.

Case summary

A 49-year-old female patient with a 2-day history of intermittent chest pain and electrocardiographic evidence of myocardial ischaemia was referred for emergency coronary angiography. This revealed severe right coronary artery (RCA) and left main (LM) coronary artery ostial vasospasm, both subsequently relieved with administration of multiple doses intracoronary nitroglycerine. Intravascular optical coherence tomography showed absence of atherosclerosis and no evidence of thrombus or dissection confirming the diagnosis of coronary artery vasospasm. Laboratory tests of the thyroid function were performed immediately after coronary angiography revealing Graves’ disease as the cause of vasospasm.

Our case represents a rare presentation of Graves’ disease-induced RCA and LM coronary artery ostial vasospasm. In patients with coronary artery vasospasm thyroid function study should be mandatory, especially in young female patients.

Learning points

- Coronary artery spasm can be induced by a hyperactive thyroid.

- When angiography demonstrates spontaneous severe multivessel coronary artery vasospasm, the presence of a systemic condition as underlying cause should be considered.

- In patients with coronary artery spasm thyroid function study should be mandatory, especially for the young female patients.

Introduction

Myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive (>50% stenosis) coronary artery disease (MINOCA) is found in approximately 6% of all patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) who are referred for coronary angiography. 1 , 2 The term MINOCA should be reserved for patients in whom there is an ischaemic basis for their clinical presentation and should be considered a ‘working diagnosis’. There are a variety of causes that can result in MINOCA and it is important that patients are appropriately diagnosed so that specific therapies to treat the underlying cause can be prescribed when possible. Thus, in the evaluation of patients presenting with clinical evidence of MI and a rise or fall in cardiac biomarkers but absence of obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) at coronary angiography, it is important to exclude (i) overt causes for the elevated troponin (e.g. sepsis, pulmonary embolism), (ii) overlooked obstructive disease (e.g. occlusion of a small coronary artery subsegment resulting from plaque disruption or embolism), and (iii) subtle non-ischaemic mechanisms of myocyte injury that can mimic MI (e.g. myocarditis). 3 Once abovementioned causes are excluded by use of available diagnostic resources, a diagnosis of MINOCA can be made.

There are disparate aetiologies causing MINOCA and they can be grouped into 2 :

- Atherosclerotic causes of myocardial necrosis (i.e. secondary to epicardial coronary artery disorders), such as atherosclerotic plaque rupture, ulceration, fissuring, erosion, or coronary dissection with non-obstructive or no CAD [MI Type 1 according to the ‘Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction’ (2018)]. 4

- Non-atherosclerotic causes of myocardial necrosis (i.e. imbalance between oxygen supply and demand), such as epicardial coronary artery spasm, coronary microvessel dysfunction, coronary embolism/thrombosis, spontaneous coronary artery dissection, or systemic conditions resulting in supply-demand mismatch (e.g. tachyarrhythmias, anaemia, hypotension, thyrotoxicosis) [MI Type 2 according to the ‘Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction’ (2018)].

We report a case of MINOCA with a rare underlying cause resulting in severe right coronary artery (RCA) and the left main (LM) ostial vasospasm.

| 2 days prior to presentation | Start of intermittent chest pain. |

| 2 h prior to presentation | Acute onset of severe chest pain, shortness of breath, and severe sweating. |

| At presentation at the referral hospital | Ongoing severe chest pain and electrocardiographic signs of ischaemia for which acute coronary syndrome medication was administered. Transfer of the patient to an interventional centre. |

| Arrival at our hospital (60 min after first medical contact) | Emergency coronary angiography was performed. This showed severe vasospasm of both ostia of the right coronary artery and left main coronary artery. After administration of intracoronary nitroglycerine, the electrocardiogram normalized and the patient was relieved from her symptoms. |

| 90 min after arrival at our hospital | Thyroid values showed a severe overactive thyroid and strumazole was started. |

| After 2 days | The patient was transferred back to the referral hospital. |

Case presentation

A 49-year-old previously healthy Caucasian woman presented to the emergency cardiac care department of a local hospital with a 2-day history of intermittent retrosternal chest pain. Since 2 h the pain worsened and she developed shortness of breath, nausea, and severe sweating. She was an active smoker and had a negative familial history for cardiovascular disease. She was not taking any regular medication and had no history of drug abuse. Physical examination documented a blood pressure of 185/92 mmHg, heart rate of 112 b.p.m., respiratory rate 25 per minute, and temperature 37.9°C. Heart sounds were normal on auscultation with no audible murmur. The rest of the clinical examination was unremarkable. The electrocardiogram showed a sinus tachycardia with widespread ST-segment depression in the inferior leads and leads V 4 –V 6 with inverted T waves and ST-segment elevation in lead aVR and V 1 ( Figure 1 ). Assuming an MI, a loading dose of aspirin 300 mg and ticagrelor 180 mg was administered and intravenous heparin 5000 IE was given. Moreover, metoprolol 2.5 mg intravenously was administered and nitroglycerine continuous infusion was started. Promptly, the patient was transferred to our hospital for emergency diagnostic coronary angiography. On arrival at the catheterization laboratory, the patient had continuous chest pain and her electrocardiogram (ECG) was unchanged. Coronary angiography revealed severe RCA and the LM ostial vasospasm ( Figure Figure2 2 A and B , Supplementary material online, Movies S1 and S2 ), with dampening of the blood pressure tracings, both subsequently relieved with administration of multiple doses (200 µg/dose) intracoronary nitroglycerine ( Figure Figure3 3 A and B , Supplementary material online, Movies S3 and S4 ). Intravascular optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed showing both arteries without atherosclerosis, thrombus or dissection ( Figure Figure3 3 C and D , Supplementary material online, Movies S5 and S6 ). Finally, left ventricular angiography showed no wall motion abnormalities ( Supplementary material online, Movie S7 ). The patient was free of symptoms when she left the catheterization laboratory and the ECG was normalized.

Admission electrocardiogram.

Coronary angiography showing severe right coronary artery (red arrow, A ) and left main ostial vasospasm (red arrow, B ).

Coronary angiography after administration of nitroglycerine of the right coronary artery ( A ) and left coronary artery ( B ) and intravascular optical coherence tomography of the right coronary artery ( C ) and left coronary artery ( D ) showing absence of atherosclerosis, thrombus, or dissection.

Further investigation revealed a Troponin T maximum of 0.451 µg/L (range 0–0.05 µg/L), N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide of 293 ng/L (range 0–249 ng/L), elevated serum free thyroxine of 59.9 pmol/L (range 12–22 pmol/L), suppressed thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) of <0.001 mE/L (range 0.5–5 mE/L), and elevated TSH receptor antibody of 20.2 E/L (range 0–1.8 E/L), confirming the diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Physical examination revealed a small nodule in the thyroid gland but no ophthalmological features. An thyroid ultrasound was not performed neither was a toxicology screen. The Burch–Wartofsky Point Scale (BWPS) score can predict the likelihood that biochemical thyrotoxicosis is thyroid storm. The BWPS is an empirically derived scoring system that takes into account the severities of symptoms of multiple organ decompensation, including thermoregulatory dysfunction, tachycardia/atrial fibrillation, disturbances of consciousness, congestive heart failure, and gastro-hepatic dysfunction, as well as the role of precipitating factors. A BWPS score of >45 represents a thyroid storm, between 25–45 an impending storm and <25 storm unlikely. Based on hyperthermia, tachycardia and gastrointestinal-hepatic dysfunction, the patients’ score was 25 indicated an impending thyroid storm. She was started on thiamazole 30 mg o.d. and within 1 day of treatment serum free thyroxine lowered from 59.9 pmol/L to 42.6 pmol/L. Therefore, iodine therapy or surgery was not considered necessary. Dual antiplatelet therapy was discontinued and a long-acting nitrate and a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker was prescribed till euthyroidism was restored. At telephone follow-up 1 week after discharge, she was free of symptoms and she experienced no side effects of the medication. As she was a labour migrant, she returned to her home country shortly thereafter.

This report illustrates a case of multivessel coronary artery spasm secondary to Graves’ disease. In our case, the presence of ST depression ≥1 mm in six or more surface leads, coupled with ST-segment elevation in aVR and/or V1, suggested multivessel ischaemia or LM coronary artery obstruction. Emergent coronary angiography was performed and showed severe ostial vasospasm of the RCA. To exclude the possibility of catheter-induced vasospasm, the initial visualization of the left coronary artery was performed by a non-selective injection which clearly showed severe vasospasm of the ostium of the LM. This severe ostial vasospasm of the RCA and the LM only improved after administration of multiple doses of intracoronary nitroglycerine. Hereafter, we decided to perform an OCT to rule out an atherosclerotic cause of myocardial necrosis. Optical coherence tomography showed a normal vessel wall with a typical three-layer appearance visible in both coronary arteries. 5 Additional laboratory testing revealed hyperthyroidism as a cause of multivessel coronary artery spasm. Although several reports of hyperthyroidism-associated angina pectoris (secondary to coronary spasm) have appeared, to our knowledge, this is one of the few cases with angiographically documented multivessel coronary artery spasm and the first report describing the use of intracoronary imaging with OCT.

Graves thyrotoxicosis is an autoimmune disease and is the most common cause of thyrotoxicosis. It is known that hyperthyroidism can cause coronary artery spasm, in particular in patients with Graves’ disease as was the case in our patient. Multiple hypothetical pathophysiological pathways have been suggested for the mechanism of thyroid hormone-induced coronary artery spasm. Hyperthyroidism can lead to a hyperkinetic circulatory system with tachycardia, increased pulse pressure, and decreased peripheral resistance secondary to vasorelaxation. 6 Along with a hypersensitivity to vasoconstrictive agents, this general hypermetabolic state precipitates an imbalance between blood supply and oxygen demand during a thyrotoxic state. 7 The exaggerated vascular reactivity is secondary to an excessive endothelial nitric oxide production and enhanced sensitivity of the endothelial component which can lead to coronary artery spasm in some patients. 6 Controlling thyroid activity will alleviate symptoms and correct the vascular abnormalities without the need of invasive interventions. In our case, laboratory tests of the thyroid function were only performed immediately after coronary angiography. Invasive coronary vascular imaging (intravascular ultrasound or OCT) can help to discriminate between an atherosclerotic vs. non-atherosclerotic cause of myocardial necrosis. Moreover, in MINOCA patients left ventricular angiography, echocardiography, or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging can rule out takotsubo cardiomyopathy or other underlying causes when there is no evident vasospasm at coronary angiography.

In a review by Al Jaber et al . 8 evaluating hyperthyroidism-associated angina pectoris, it was shown that the age range of reported patients was 44–75 years, with female predominance, more commonly in Asian patients, and the time from symptom onset to diagnosis varied between days to 8 months. Moreover, hyperthyroid manifestations may be mild or absent. The pattern of cardiac presentation included angina pectoris, MI, cardiogenic shock, ventricular tachyarrythmias, cardiac arrest, and/or pulmonary oedema. Importantly, a review of coronary angiograms in patients with an overactive thyroid showed that the LM coronary artery was significantly more involved than the RCA. 9 Delay in diagnosis of hyperthyroidism-induced myocardial necrosis in these patients may result in complications and unnecessary interventions. With appropriate antithyroid therapy, the prognosis of patients with hyperthyroidism-associated angina pectoris is excellent. 9 , 10

Lead author biography

Margo Klomp, MD, PhD, MBA, is a General Cardiologist at the Dijklander Hospital in Noord-Holland, the Netherlands with specific interests in management.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Supplementary Material

Ytaa191_supplementary_data, acknowledgements.

Both authors received no funding in the development of this case report

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data .

Consent: The author/s confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including image(s) andassociated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

- Store finder

Cardiovascular disease case studies

Read international case studies of cardiovascular disease prevention in a joint report by the BHF and Public Health England.

The UK has made progress on bringing down the premature death rate associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) in recent years. But CVD still affects around seven million people in the UK, is responsible for one in five premature deaths and is estimated to cost the healthcare economy £9 billion each year.

To continue to make progress in preventing CVD, we can learn from other nations who have successfully delivered programmes that improve cardiovascular health.

In 2018, jointly with Public Health England, we commissioned a report identifying successful CVD prevention programmes from around the world, produced by public health consultancy group Solutions for Public Health.

The report, International Cardiovascular Disease Prevention case studies, outlines ten case studies that illustrate approaches that may be applicable and effective within the UK.

Download the report [PDF]

International context of CVD prevention

Ten case studies are detailed in the report, including:

- The COACH programme in Australia where trained nurses coach people who have, or are at high risk of developing, CVD over the phone

- Hypertension Canada, which aims to train healthcare professionals to diagnose hypertension and follow evidence-based guidelines on managing the condition

- The Million Hearts initiative in the US, which aims to align CVD prevention efforts across 50 states by focusing on a small set of evidence-based priorities such as controlling blood pressure and smoking cessation

- The CHAP initiative in Canada, where older people were encouraged to attend volunteer-run sessions to encourage them to become more aware of their cardiovascular risk

- The HONU project in the US, where people at risk of CVD were assigned a health coach to support lifestyle change, and initiatives were set up in workplaces and at community and government level to improve diet and activity levels

Alongside the case studies, the report also makes recommendations for how to implement effective CVD prevention programmes in the UK, and provides background on current CVD prevention programmes in England.

You can access the report now for the full details on these case studies and recommendations.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Coronary heart disease as a case study in prevention: potential role of incentives

Affiliation.

- 1 Division of Cardiology, University of Vermont College of Medicine, University Health Center Campus, 1 S. Prospect St, Burlington, VT 05401, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 22285317

- DOI: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.12.025

Coronary atherosclerosis is a complex entity with behavioral, genetic and environmental antecedents. Most risk factors for coronary heart disease have a behavioral component. These include tobacco use, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes and physical inactivity. The role of monetary incentives to encourage healthful behaviors related to the prevention and treatment of coronary heart disease has received little attention. In this review, the potential role of monetary incentives to prevent or treat coronary heart disease is discussed. In particular, the potential role of providing incentives for patients to participate in cardiac rehabilitation (CR), a multi-risk intervention, is highlighted.

Copyright © 2011. Published by Elsevier Inc.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Risk factors of Hong Kong Chinese patients with coronary heart disease. Chair SY, Lee SF, Lopez V, Ling EM. Chair SY, et al. J Clin Nurs. 2007 Jul;16(7):1278-84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01383.x. J Clin Nurs. 2007. PMID: 17584346

- Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs. Savage PD, Banzer JA, Balady GJ, Ades PA. Savage PD, et al. Am Heart J. 2005 Apr;149(4):627-31. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.07.037. Am Heart J. 2005. PMID: 15990744

- Potential benefits of weight loss in coronary heart disease. Ades PA, Savage PD. Ades PA, et al. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014 Jan-Feb;56(4):448-56. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.09.009. Epub 2013 Oct 9. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014. PMID: 24438737 Review.

- Impact of cardiac rehabilitation on metabolic syndrome in Iranian patients with coronary heart disease: the role of obesity. Kabir A, Sarrafzadegan N, Amini A, Aryan RS, Kerahroodi FH, Rabiei K, Taghipour HR, Moghimi M. Kabir A, et al. Rehabil Nurs. 2012 Mar-Apr;37(2):66-73. doi: 10.1002/RNJ.00012. Rehabil Nurs. 2012. PMID: 22434616

- Controlling health care costs in the military: the case for using financial incentives to improve beneficiary personal health indicators. Naito NA, Higgins ST. Naito NA, et al. Prev Med. 2012 Nov;55 Suppl:S113-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.06.022. Epub 2012 Jul 2. Prev Med. 2012. PMID: 22766007 Review.

- Early Diagnosis and Treatment of Coronary Heart Disease with Image Features of Optical Coherence Tomography under Adaptive Segmentation Algorithm. Lin C. Lin C. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022 Aug 8;2022:1261259. doi: 10.1155/2022/1261259. eCollection 2022. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022. PMID: 35979043 Free PMC article.

- Identification of hub genes and their correlation with immune infiltration in coronary artery disease through bioinformatics and machine learning methods. Huang KK, Zheng HL, Li S, Zeng ZY. Huang KK, et al. J Thorac Dis. 2022 Jul;14(7):2621-2634. doi: 10.21037/jtd-22-632. J Thorac Dis. 2022. PMID: 35928610 Free PMC article.

- Surface Functionalized Magnetic Nanoparticles as a Selective Sorbent for Affinity Fishing of PPAR-γ Ligands from Choerospondias axillaris . Chi M, Qin K, Cao L, Zhang M, Su Y, Gao X. Chi M, et al. Molecules. 2022 May 13;27(10):3127. doi: 10.3390/molecules27103127. Molecules. 2022. PMID: 35630609 Free PMC article.

- Construction of genetic classification model for coronary atherosclerosis heart disease using three machine learning methods. Peng W, Sun Y, Zhang L. Peng W, et al. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022 Feb 12;22(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12872-022-02481-4. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022. PMID: 35151267 Free PMC article.

- Classifiers for Predicting Coronary Artery Disease Based on Gene Expression Profiles in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. Liu J, Wang X, Lin J, Li S, Deng G, Wei J. Liu J, et al. Int J Gen Med. 2021 Sep 15;14:5651-5663. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S329005. eCollection 2021. Int J Gen Med. 2021. PMID: 34552349 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- ClinicalKey

- Elsevier Science

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland

Respiratory viruses continue to circulate in Maryland, so masking remains strongly recommended when you visit Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. To protect your loved one, please do not visit if you are sick or have a COVID-19 positive test result. Get more resources on masking and COVID-19 precautions .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Coronary Heart Disease

What are the coronary arteries.

Coronary arteries supply blood to the heart muscle. Like all other tissues in the body, the heart muscle needs oxygen-rich blood to function, and oxygen-depleted blood must be carried away. The coronary arteries run along the outside of the heart and have small branches that supply blood to the heart muscle.

What are the different coronary arteries?

The 2 main coronary arteries are the left main and right coronary arteries.

Left main coronary artery (LMCA). The left main coronary artery supplies blood to the left side of the heart muscle (the left ventricle and left atrium). The left main coronary artery divides into branches:

The left anterior descending artery branches off the left coronary artery and supplies blood to the front of the left side of the heart.

The circumflex artery branches off the left coronary artery and encircles the heart muscle. This artery supplies blood to the lateral side and back of the heart.

Right coronary artery (RCA). The right coronary artery supplies blood to the right ventricle, the right atrium, and the SA (sinoatrial) and AV (atrioventricular) nodes, which regulate the heart rhythm. The right coronary artery divides into smaller branches, including the right posterior descending artery and the acute marginal artery.

Additional smaller branches of the coronary arteries include the obtuse marginal (OM), septal perforator (SP), and diagonals.

Why are the coronary arteries important?

Since coronary arteries deliver blood to the heart muscle, any coronary artery disorder or disease can reduce the flow of oxygen and nutrients to the heart, which may lead to a heart attack and possibly death. Atherosclerosis is inflammation and a buildup of plaque in the inner lining of an artery causing it to narrow or become blocked. It is the most common cause of heart disease.

What is coronary artery disease?

Coronary heart disease, or coronary artery disease (CAD), is characterized by inflammation and the buildup of and fatty deposits along the innermost layer of the coronary arteries. The fatty deposits may develop in childhood and continue to thicken and enlarge throughout the life span. This thickening, called atherosclerosis, narrows the arteries and can decrease or block the flow of blood to the heart.

The American Heart Association estimates that over 16 million Americans suffer from coronary artery disease--the number one killer of both men and women in the U.S.

What are the risk factors for coronary artery disease?

Risk factors for CAD often include:

High LDL cholesterol , high triglycerides levels, and low HDL cholesterol

High blood pressure (hypertension)

Physical inactivity

High saturated fat diet

Family history

Controlling risk factors is the key to preventing illness and death from CAD.

What are the symptoms of coronary artery disease?

The symptoms of coronary heart disease will depend on the severity of the disease. Some people with CAD have no symptoms, some have episodes of mild chest pain or angina, and some have more severe chest pain.

If too little oxygenated blood reaches the heart, a person will experience chest pain called angina. When the blood supply is completely cut off, the result is a heart attack, and the heart muscle begins to die. Some people may have a heart attack and never recognize the symptoms. This is called a "silent" heart attack.

Symptoms of coronary artery disease include:

Heaviness, tightness, pressure, or pain in the chest behind the breastbone

Pain spreading to the arms, shoulders, jaw, neck, or back

Shortness of breath

Weakness and fatigue

How is coronary artery disease diagnosed?

In addition to a complete medical history and physical exam, tests for coronary artery disease may include the following:

Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). This test records the electrical activity of the heart, shows abnormal rhythms (arrhythmias), and detects heart muscle damage.

Stress test (also called treadmill or exercise ECG). This test is given while you walk on a treadmill to monitor the heart during exercise. Breathing and blood pressure rates are also monitored. A stress test may be used to detect coronary artery disease, or to determine safe levels of exercise after a heart attack or heart surgery. This can also be done while resting using special medicines that can synthetically place stress on the heart.

Cardiac catheterization . With this procedure, a wire is passed into the coronary arteries of the heart and X-rays are taken after a contrast agent is injected into an artery. It's done to locate the narrowing, blockages, and other problems.

Nuclear scanning. Radioactive material is injected into a vein and then is observed using a camera as it is taken up by the heart muscle. This indicates the healthy and damaged areas of the heart.

Treatment for coronary heart disease

Treatment may include:

Modification of risk factors. Risk factors that you can change include smoking, high cholesterol levels, high blood glucose levels, lack of exercise, poor dietary habits, being overweight, and high blood pressure.

Medicines. Medicine that may be used to treat coronary artery disease include:

Antiplatelets. These decrease blood clotting. Aspirin, clopidogrel, ticlopidine, and prasugrel are examples of antiplatelets.

Antihyperlipidemics. These lower lipids (fats) in the blood, particularly low density lipid (LDL) cholesterol. Statins are a group of cholesterol-lowering medicines, and include simvastatin, atorvastatin, and pravastatin, among others. Bile acid sequestrants--colesevelam, cholestyramine and colestipol--and nicotinic acid (niacin) are other medicines used to reduce cholesterol levels.

Antihypertensives. These lower blood pressure. Several different groups of medicines work in different ways to lower blood pressure.

Coronary angioplasty. With this procedure, a balloon is used to create a bigger opening in the vessel to increase blood flow. Although angioplasty is done in other blood vessels elsewhere in the body, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) refers to angioplasty in the coronary arteries to permit more blood flow into the heart. PCI is also called percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA). There are several types of PCI procedures, including:

Balloon angioplasty. A small balloon is inflated inside the blocked artery to open the blocked area.

Coronary artery stent. A tiny mesh coil is expanded inside the blocked artery to open the blocked area and is left in place to keep the artery open.

Atherectomy. The blocked area inside the artery is cut away by a tiny device on the end of a catheter.

Laser angioplasty. A laser used to "vaporize" the blockage in the artery.

Coronary artery bypass . Most commonly referred to as simply "bypass surgery" or CABG (pronounced "cabbage"), this surgery is often done in people who have chest pain (angina) and coronary artery disease. During the surgery, a bypass is created by grafting a piece of a vein above and below the blocked area of a coronary artery, enabling blood to flow around the blockage. Veins are usually taken from the leg, but arteries from the chest or arm may also be used to create a bypass graft. Sometimes, multiple bypasses may be needed to fully restore blood flow to all regions of the heart.

Find a Doctor

Specializing In:

- Coronary Angiography

- Cardiac Disease

- Cardiovascular Disease

Find a Treatment Center

Find Additional Treatment Centers at:

- Howard County Medical Center

- Sibley Memorial Hospital

- Suburban Hospital

Request an Appointment

Calculating Your Cholesterol

Risk Factors for Heart Disease: Don't Underestimate Stress

Alcohol and Heart Health: Separating Fact from Fiction

Related Topics

- Heart and Vascular

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Coronary artery aneurysms: a clinical case report and literature review supporting therapeutic choices.

1. Introduction

1.1. definition and classification of coronary artery aneurysms, 1.2. risk factors, 1.3. clinical presentation, 1.4. diagnostic skills, 1.5. treatment, 1.6. caas in kawasaki disease, 2. clinical case presentation, 2.1. medical history, 2.2. examinations, 2.3. management, 3. conclusions, author contributions, conflicts of interest.

- Li, D.; Wu, Q.; Sun, L.; Song, Y.; Wang, W.; Pan, S.; Luo, G.; Liu, Y.; Qi, Z.; Tao, T.; et al. Surgical treatment of giant coronary artery aneurysm. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005 , 130 , 817–821. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Morita, H.; Ozawa, H.; Yamazaki, S.; Yamauchi, Y.; Tsuji, M.; Katsumata, T.; Ishizaka, N. A case of giant coronary artery aneurysm with fistulous connection to the pulmonary artery: A case report and review of the literature. Intern. Med. 2012 , 51 , 1361–1366. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Waye, P.S.; Fisher, L.D.; Litwin, P.; A Vignola, P.; Judkins, M.P.; Kemp, H.G.; Mudd, J.G.; Gosselin, A.J. Aneurysmal coronary artery disease. Circulation 1983 , 67 , e134–e138. [ Google Scholar ]

- Núñez-Gil, I.J.; Nombela-Franco, L.; Bagur, R.; Bollati, M.; Cerrato, E.; Alfonso, E.; Liebetrau, C.; De la Torre Hernandez, J.M.; Camacho, B.; Mila, R.; et al. Rationale and design of a multicenter, international and collaborative Coronary Artery Aneurysm Reg-istry (CAAR). Clin. Cardiol. 2017 , 40 , e580–e585. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Newburger, J.W.; Takahashi, M.; Gerber, M.A.; Gewitz, M.H.; Tani, L.Y.; Burns, J.C.; Shulman, S.T.; Bolger, A.F.; Ferrieri, P.; Baltimore, R.S.; et al. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Long-Term Management of Kawasaki Disease: A Scientific Statement for Health Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017 , 135 , e927–e999. [ Google Scholar ]

- Befeler, B.; Aranda, J.M.; Embi, A.; Mullin, F.L.; El-Sherif, N.; Lazzara, R. Coronary artery aneurysms. Study of their etiology, clinical course and effect on left ventricular function and prognosis. Am. J. Med. 1977 , 62 , e597–e607. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Abou Sherif, S.; Ozden Tok, O.; Taşköylü, Ö.; Goktekin, O.; Kilic, I.D. Coronary Artery Aneurysms: A Review of the Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2017 , 4 , 24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kawsara, A.; Núñez Gil, I.J.; Alqahtani, F.; Moreland, J.; Rihal, C.S.; Alkhouli, M. Management of coronary artery aneurysms. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018 , 11 , e1211–e1223. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cohen, P.; O’Gara, P.T. Coronary artery aneurysms: A review of the natural history, pathophysiology, and management. Cardiol. Rev. 2008 , 16 , e301–e304. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lamblin, N.; Bauters, C.; Hermant, X.; Lablanche, J.M.; Helbecque, N.; Amouyel, P. Polymorphisms in the promoter regions of MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-9 and MMP-12 genes as determinants of aneurys-mal coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002 , 40 , 43–48. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Aoki, J.; Kirtane, A.; Leon, M.B.; Dangas, G. Coronary artery aneurysms after drug-eluting stent implantation. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv 2008 , 1 , 14–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Kim, U.; Seol, S.H.; Kim, D.I.; Kim, D.K.; Jang, J.S.; Yang, T.H.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, D.S.; Min, H.K.; Choi, K.J. Clinical outcomes and the risk factors of coronary artery aneurysms that developed after drug-eluting stent implantation. Circ. J. 2011 , 75 , 861–867. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fujino, Y.; Attizzani, G.F.; Nakamura, S.; Costa, M.A.; Bezerra, H.G. Coronary artery aneurysms after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation: Multimodality imaging evaluation. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013 , 6 , 423–424. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Vassilev, D.; Hazan, M.; Dean, L. Aneurysm formation after drug-eluting balloon treatment of drug-eluting in-stent restenosis: First case report. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2012 , 80 , 1223–1226. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Gargiulo, G.; Mangiameli, A.; Granata, F.; Ohno, Y.; Chisari, A.; Capodanno, D.; Tamburino, C.; La Manna, A. New-onset coronary aneurism and late-acquired incomplete scaffold apposition after full polymer jacket of a chronic total occlusion with bioresorbable scaffolds. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015 , 8 , e41–e43. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cereda, A.F.; Canova, P.A.; Oreglia, J.A.; Soriano, F.S. Coronary Artery Aneurysm After Bioresorbable Scaffold Implantation in a Woman With an Acute Coronary Syndrome. J. Invasive Cardiol. 2017 , 29 , E77–E78. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fabbiocchi, F.; Calligaris, G.; Bartorelli, A.L. Progressive growth of coronary aneurysms after bioresorbable vascular scaffold implantation: Successful treatment with OCT-guided exclusion using covered stents. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021 , 97 , E676–E679. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fabbiocchi, F.; Calligaris, G.; Bartorelli, A.L. Coronary evaginations and peri-scaffold aneurysms following implantation of bioresorbable scaffolds: Incidence, outcome, and optical coherence tomography analysis of possible mechanisms. Eur. Heart J. 2016 , 37 , 2040–2049. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chua, S.K.; Cheng, J.J. Coronary artery aneurysm after implantation of a bioresorbable vascular scaffold: Case report and literature review. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017 , 90 , E41–E45. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Patel, A.; Nazif, T.; Stone, G.W.; Ali, Z.A. Intraluminal bioresorbable vascular scaffold dismantling with aneurysm formation leading to very late thrombosis. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015 , 86 , 678–681. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Şerban, R.; Scridon, A.; Dobreanu, D.; Elkaholut, A. Coronary artery aneurysm formation within everolimus-eluting bioresorbable stent. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014 , 177 , e4–e5. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Şerban, R.; Scridon, A.; Dobreanu, D.; Elkaholut, A. Coronary Artery Aneurysm: Evaluation, Prognosis, and Proposed Treatment Strategies. Heart Views 2019 , 20 , e101–e108. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chrissoheris, M.P.; Donohue, T.J.; Young, R.S.; Ghantous, A. Coronary artery aneurysms. Cardiol. Rev. 2008 , 16 , e116–e123. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Krüger, D.; Stierle, U.; Herrmann, G.; Simon, R.; Sheikhzadeh, A. Exercise-induced myocardial ischemia in isolated coronary artery ectasias and aneurysms (“dilated coronopathy”). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999 , 34 , e1461–e1470. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Núñez-Gil, I.J.; Cerrato, E.; Bollati, M.; Nombela-Franco, L.; Terol, B.; Alfonso-Rodríguez, E.; Freire, S.J.C.; Villablanca, P.A.; Santos, I.J.A.; de la Torre Hernández, J.M.; et al. CAAR investigators. Coronary artery aneurysms, insights from the international coronary artery aneurysm registry (CAAR). Int. J. Cardiol. 2020 , 299 , 49–55. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pavani, M.; Cerrato, E.; Latib, A.; Ryan, N.; Calcagno, S.; Rolfo, C.; Ugo, F.; Ielasi, A.; Escaned, J.; Tespili, M. Acute and long-term outcomes after polytetrafluoroethylene or pericardium covered stenting for grade 3 coronary artery perforations: Insights from G3-CAP registry. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018 , 92 , 1247–1255. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- LaMotte, L.C.; Mathur, V.S. Atherosclerotic coronary artery aneurysms: Eight-year angiographic follow-up. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2000 , 27 , e72–e73. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maehara, A.; Mintz, G.S.; Ahmed, J.M.; Fuchs, S.; Castagna, M.T.; Pichard, A.D.; Satler, L.F.; Waksman, R.; O Suddath, W.; Kent, K.M.; et al. An intravascular ultrasound classification of angiographic coronary artery aneurysms. Am. J. Cardiol. 2001 , 88 , e365–e370. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fathelbab, H.; Freire, S.J.C.; Jiménez, J.L.; Piris, R.C.; Menchero, A.E.G.; Garrido, J.R.; Fernández, J.F.D. Detection of spontaneous coronary artery spasm with optical coherence tomography in a patient with acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc. Revascularization Med. 2017 , 18 , e7–e9. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Murthy, P.A.; Mohammed, T.L.; Read, K.; Gilkeson, R.C.; White, C.S. MDCT of coronary artery aneurysms. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2005 , 184 (Suppl. S3), S19–S20. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Núñez-Gil, I.J.; Terol, B.; Feltes, G.; Nombela-Franco, L.; Salinas, P.; Escaned, J.; Jiménez-Quevedo, P.; Gonzalo, N.; Vivas, D.; Bautista, D.; et al. Coronary aneurysms in the acute patient: Incidence, characterization and long-term management results. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2018 , 19 , 589–596. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- D’Ascenzo, F.; Saglietto, A.; Ramakrishna, H.; Andreis, A.; Jiménez-Mazuecos, J.M.; Nombela-Franco, L.; Cerrato, E.; Liebetrau, C.; Alfonso-Rodríguez, E.; Bagur, R.; et al. CAAR Investigators. Usefulness of oral anticoagulation in patients with coronary aneurysms: Insights from the CAAR registry. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021 , 98 , 864–871. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Khubber, S.; Chana, R.; Meenakshisundaram, C.; Dhaliwal, K.; Gad, M.; Kaur, M.; Banerjee, K.; Verma, B.R.; Shekhar, S.; Khan, M.Z.; et al. Coronary artery aneurysms: Outcomes following medical, percutaneous interventional and surgical management. Open Heart 2021 , 8 , e001440. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Joo, H.J.; Yu, C.W.; Choi, R.; Park, J.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, J.S.; Choi, Y.J.; Park, J.H.; Hong, S.J.; Lim, D.S. Clinical outcomes of patients with coronary artery aneurysm after the first generation drug-eluting stent implantation. Cathet Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018 , 92 , E235–E245. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bhoopalan, K.; Rajendran, R.; Alagarsamy, S.; Kesavamoorthy, N. Successful extraction of refractory thrombus from an ectasic coronary artery using stent retriever during primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: A case report. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2019 , 3 , yty161. [ Google Scholar ]

- Warisawa, T.; Naganuma, T.; Nakumura, S.; Hartmann, M.; Stoel, M.G.; Louwerenburg, J.H.W.; Basalus, M.W.; Von Birgelen, C.; Koo, B.K. How should I treat multiple coronary aneurysms with severe stenoses? EuroIntervention 2015 , 11 , 843–846. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Barioli, A.; Pellizzari, N.; Favero, L.; Cernetti, C. Unconventional treatment of a giant coronary aneurysm presenting as ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A case report. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2021 , 5 , ytab385. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- De Hous, N.; Haine, S.; Oortman, R.; Laga, S. Alternative approach for the surgical treatment of left main coronary artery aneurysm. Ann Thorac Surg 2019 , 108 , e91–e93. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Burns, J.C.; Glode, M.P.; Clarke, S.H.; Wiggins, J., Jr.; Hathaway, W.E. Coagulopathy and platelet activation in Kawasaki syndrome: Identification of patients at high risk for development of coronary artery aneurysms. J. Pediatr. 1984 , 105 , 206–211. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Franco, A.; Shimizu, C.; Tremoulet, A.H.; Burns, J.C. Memory Tcells and characterization of peripheral T-cell clones in acute Kawasaki disease. Autoimmunity 2010 , 43 , 317–324. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rowley, A.H.; Baker, S.C.; Shulman, S.T.; Garcia, F.L.; Fox, L.M.; Kos, I.M.; Crawford, S.E.; Russo, P.A.; Hammadeh, R.; Takahashi, K.; et al. RNA-containing cytoplasmic inclusion bodies in ciliated bronchial epithelium months to years after acute Kawasaki disease. PLoS ONE 2008 , 3 , e1582. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Rowley, A.H.; Baker, S.C.; Shulman, S.T.; Rand, K.H.; Tretiakova, M.S.; Perlman, E.J.; Garcia, F.L.; Tajuddin, N.F.; Fox, L.M.; Huang, J.H. Ultrastructural, immunofluorescence, and RNA evidence support the hypothesis of a “new” virus associated with Kawasaki disease. J. Infect. Dis. 2011 , 203 , 1021–1030. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Printz, B.F.; Sleeper, L.A.; Newburger, J.W.; Minich, L.L.; Bradley, T.; Cohen, M.S.; Frank, D.; Li, J.S.; Margossian, R.; Shirali, G.; et al. Noncoronary cardiac abnormalities are associated with coronary artery dilation and with laboratory inflammatory markers in acute Kawasaki disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011 , 57 , 86–92. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Muniz, J.C.; Dummer, K.; Gauvreau, K.; Colan, S.D.; Fulton, D.R.; Newburger, J.W. Coronary artery dimensions in febrile children without Kawasaki disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013 , 6 , 239–244. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bratincsak, A.; Reddy, V.D.; Purohit, P.J.; Tremoulet, A.H.; Molkara, D.P.; Frazer, J.R.; Dyar, D.; Bush, R.A.; Sim, J.Y.; Sang, N.; et al. Coronary artery dilation in acute Kawasaki disease and acute illnesses associated with fever. Pediatr. Infect. Dis J. 2012 , 31 , 924–926. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Sannino, M.; Nicolai, M.; Infusino, F.; Giulio, L.; Usai, T.L.; Biscotti, G.; Azzarri, A.; De Angelis D’Ossat, M.; Calcagno, S.; Calcagno, S. Coronary Artery Aneurysms: A Clinical Case Report and Literature Review Supporting Therapeutic Choices. J. Clin. Med. 2024 , 13 , 5348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13185348

Sannino M, Nicolai M, Infusino F, Giulio L, Usai TL, Biscotti G, Azzarri A, De Angelis D’Ossat M, Calcagno S, Calcagno S. Coronary Artery Aneurysms: A Clinical Case Report and Literature Review Supporting Therapeutic Choices. Journal of Clinical Medicine . 2024; 13(18):5348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13185348

Sannino, Michele, Matteo Nicolai, Fabio Infusino, Luciani Giulio, Tommaso Leo Usai, Giovanni Biscotti, Alessandro Azzarri, Marina De Angelis D’Ossat, Sergio Calcagno, and Simone Calcagno. 2024. "Coronary Artery Aneurysms: A Clinical Case Report and Literature Review Supporting Therapeutic Choices" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 18: 5348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13185348

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

On examination, the temperature was 36.4°C, the heart rate 103 beats per minute, the blood pressure 79/51 mm Hg, the respiratory rate 30 breaths per minute, and the oxygen saturation 99% while ...

A 67-year-old woman sought emergency medical care due to prolonged chest pain. In April 2009 the patient had prolonged chest pain and at that time she sought medical care. She was admitted at the hospital and diagnosed with myocardial infarction. The patient had hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and was a smoker.

In the case discussed, 15 years after coronary disease stratification and percutaneous coronary intervention, the patient had angina on moderate exertion, suggesting that the therapeutic strategy with percutaneous and drug revascularization, to control risk factors, did not prevent disease progression. ... The microscopic study of the coronary ...

A 57 year-old male lorry driver, presented to his local emergency department with a 20-minute episode of diaphoresis and chest pain. The chest pain was central, radiating to the left arm and crushing in nature. The pain settled promptly following 300 mg aspirin orally and 800 mcg glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) spray sublingually administered by ...

Presentation of Case. Dr. Jacqueline B. Henson (Medicine): A 54-year-old man was evaluated at this hospital after cardiac arrest associated with ventricular fibrillation. The patient had been in ...

The main diagnostic hypothesis for this clinical case is of acute coronary syndrome. ... Sudden death risk in overt coronary heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1987; 113 (3):799-804. [Google Scholar] 6.

Dr. John Conte performed the coronary bypass surgery. Of interest is the fact that in 1999, Dr. Conte published a case report of the first ever successful bloodless lung transplant in a Jehovah's Witness patient. In this case presented here, he decided the patient would be best served by performing an "off-pump" cardiac surgery where the ...

Both serial 12-lead ECG and highly sensitive cardiac troponin T testing should be performed before excluding ongoing ischemic coronary artery disease. Prior to stress testing, the patient should be chest pain free for 24 hours, without dynamic 12-lead ECG changes, and the highly sensitive cardiac troponin T level should be negative or trending ...

Dr. Amy A. Sarma: A 54-year-old man was evaluated at this hospital because of new heart failure. One month before this evaluation, a nonproductive cough developed after the patient took a business ...

This chapter illustrates various general issues in genetic epidemiology in relation to coronary artery disease (CAD). This is a disease strongly influenced by environmental/lifestyle factors, such as smoking, but with substantial estimated heritability. ... Coronary artery disease: an example case study Methods Mol Biol. 2011:713:215-25. doi ...

In summary, the presence of mild dyslipidemia, high blood pressure, cigarette smoking, obesity, and a family history was sufficient to induce ischemic heart disease at such a young age. <Learning objective: This case report reveals an exceptionally young Caucasian man presenting with stable angina and found to have multivessel coronary disease ...

Introduction. This clinical case refers to an 83-year-old man with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and shows that implementation of appropriate medical therapy according to the European Society of Cardiology/Heart Failure Association (ESC/HFA) guidelines improves symptoms and quality of life. 1 The case also illustrates that optimization of glucose metabolism with a more lenient ...

At the American Heart Association (AHA) Annual Scientific Sessions, held virtually from November 13 to 15, 2021, I had the honor to work with 2 special people to help tell their incredible stories of survival following catastrophic cardiovascular events. ... Heart disease and stroke statistics—2021 update: a report from the American Heart ...

Mortality from cardiovascular disease, especially coronary artery disease (CAD), has dramatically decreased in the past few decades. 3, 4 While public health initiatives aimed at primary prevention have certainly led to some of these gains, advances in treatment for patients with CAD have accounted for a significant portion. 5, 6

In this case, a patient with known history of coronary artery disease presented with worsening of shortness of breath with lower extremity edema and jugular venous distension along with crackles in the lung. The sign and symptoms along with labs and imaging findings point to diagnosis of heart failure with reduced EF (HFrEF).

Jonathan chooses to focus on losing weight, reducing salt intake and reducing alcohol intake as he feels these are the most important to him. The questions raised in this chapter include queries regarding the Jonathan's risk factors for heart disease, main considerations of a cardio-protective diet, definition of troponin, the nutrition and ...

Introduction. Myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive (>50% stenosis) coronary artery disease (MINOCA) is found in approximately 6% of all patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) who are referred for coronary angiography. 1, 2 The term MINOCA should be reserved for patients in whom there is an ischaemic basis for their clinical presentation and should be considered a ...

Cardiovascular disease case studies. Read international case studies of cardiovascular disease prevention in a joint report by the BHF and Public Health England. The UK has made progress on bringing down the premature death rate associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) in recent years. But CVD still affects around seven million people in ...

Coronary atherosclerosis is a complex entity with behavioral, genetic and environmental antecedents. Most risk factors for coronary heart disease have a behavioral component. These include tobacco use, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes and physical inactivity. The r …

An epidemic of coronary heart disease (CHD) began during the 20th century in most industrialized countries, where CHD is a leading cause of mortality among adults. 1 Developing countries show the beginnings of the same epidemic. Reliable information on population incidence, prevalence, and case-fatality rates of CHD is essential to understanding, treating, and controlling the epidemic but is ...

Forty-eight patients with moderate to severe coronary heart disease were randomized to an intensive lifestyle change group or to a usual-care control group, and 35 completed the 5-year follow-up quantitative coronary arteriography. Setting.— Two tertiary care university medical centers. Intervention.—

Request an Appointment. 410-955-5000 Maryland. 855-695-4872 Outside of Maryland. +1-410-502-7683 International. Find a Doctor. A person with coronary heart disease has an accumulation of fatty deposits in the coronary arteries. These deposits narrow the arteries and can decrease or block the flow of blood to the heart.

Relative risk estimates of coronary heart disease (top) and stroke (bottom) for systolic blood pressure (BP) reduction of 10 mm Hg or diastolic BP reduction of 5 mm Hg in clinical trials meta-analysis and corresponding difference in meta-analysis of observational cohort studies. CHD indicates coronary heart disease; CV, cardiovascular; and RR ...

Coronary artery aneurysms (CAAs) are uncommon but significant cardiovascular abnormalities characterized by an abnormal increase in vascular diameter. CAAs are classified based on their shape as either saccular or fusiform, and their causes can range from atherosclerosis, Kawasaki disease, to congenital and iatrogenic factors. CAAs often present asymptomatically, but when symptoms occur, they ...

2.1. Study population and coronary segmentation. The ASOCA dataset [] comprises 40 CAD cases, from which we excluded one diseased case due to extreme stenosis in the left anterior descending (LAD) artery.Of the 39 left main coronary trees studied, 20 had no significant stenosis, 12 were moderately stenosed and 7 had severe stenoses.

Key Points. Question Are seafood and plant-derived ω-3 fats related to first coronary heart disease (CHD) events?. Findings In a consortium of 19 studies, biomarkers of seafood and plant-derived ω-3 fats were associated with a significantly lower risk of fatal CHD. In contrast, associations with nonfatal myocardial infarction were generally less robust.