Walter Benjamin 1940

On the Concept of History

Source : http://www.efn.org/~dredmond/Theses_on_History.html ; Translation : © 2005 Dennis Redmond; CopyLeft : translation used with permission, Creative Commons (Attribute & ShareAlike); Original German : Gesammelten Schriften I:2. Suhrkamp Verlag. Frankfurt am Main, 1974; Transcribed : by Andy Blunden .

Translator’s Note : Jetztzeit was translated as “here-and-now,” in order to distinguish it from its polar opposite, the empty and homogenous time of positivism. Stillstellung was rendered as “zero-hour,” rather than the misleading “standstill”; the verb “stillstehen” means to come to a stop or standstill, but Stillstellung is Benjamin’s own unique invention, which connotes an objective interruption of a mechanical process, rather like the dramatic pause at the end of an action-adventure movie, when the audience is waiting to find out if the time-bomb/missile/terrorist device was defused or not).

It is well-known that an automaton once existed, which was so constructed that it could counter any move of a chess-player with a counter-move, and thereby assure itself of victory in the match. A puppet in Turkish attire, water-pipe in mouth, sat before the chessboard, which rested on a broad table. Through a system of mirrors, the illusion was created that this table was transparent from all sides. In truth, a hunchbacked dwarf who was a master chess-player sat inside, controlling the hands of the puppet with strings. One can envision a corresponding object to this apparatus in philosophy. The puppet called “historical materialism” is always supposed to win. It can do this with no further ado against any opponent, so long as it employs the services of theology, which as everyone knows is small and ugly and must be kept out of sight.

“Among the most noteworthy characteristics of human beings,” says Lotze, “belongs... next to so much self-seeking in individuals, the general absence of envy of each present in relation to the future.” This reflection shows us that the picture of happiness which we harbor is steeped through and through in the time which the course of our own existence has conferred on us. The happiness which could awaken envy in us exists only in the air we have breathed, with people we could have spoken with, with women who might have been able to give themselves to us. The conception of happiness, in other words, resonates irremediably with that of resurrection [ Erloesung : transfiguration, redemption]. It is just the same with the conception of the past, which makes history into its affair. The past carries a secret index with it, by which it is referred to its resurrection. Are we not touched by the same breath of air which was among that which came before? is there not an echo of those who have been silenced in the voices to which we lend our ears today? have not the women, who we court, sisters who they do not recognize anymore? If so, then there is a secret protocol [ Verabredung : also appointment] between the generations of the past and that of our own. For we have been expected upon this earth. For it has been given us to know, just like every generation before us, a weak messianic power, on which the past has a claim. This claim is not to be settled lightly. The historical materialist knows why.

The chronicler, who recounts events without distinguishing between the great and small, thereby accounts for the truth, that nothing which has ever happened is to be given as lost to history. Indeed, the past would fully befall only a resurrected humanity. Said another way: only for a resurrected humanity would its past, in each of its moments, be citable. Each of its lived moments becomes a citation a l'ordre du jour [order of the day] – whose day is precisely that of the Last Judgment.

Secure at first food and clothing, and the kingdom of God will come to you of itself. – Hegel, 1807

The class struggle, which always remains in view for a historian schooled in Marx, is a struggle for the rough and material things, without which there is nothing fine and spiritual. Nevertheless these latter are present in the class struggle as something other than mere booty, which falls to the victor. They are present as confidence, as courage, as humor, as cunning, as steadfastness in this struggle, and they reach far back into the mists of time. They will, ever and anon, call every victory which has ever been won by the rulers into question. Just as flowers turn their heads towards the sun, so too does that which has been turn, by virtue of a secret kind of heliotropism, towards the sun which is dawning in the sky of history. To this most inconspicuous of all transformations the historical materialist must pay heed.

The true picture of the past whizzes by. Only as a picture, which flashes its final farewell in the moment of its recognizability, is the past to be held fast. “The truth will not run away from us” – this remark by Gottfried Keller denotes the exact place where historical materialism breaks through historicism’s picture of history. For it is an irretrievable picture of the past, which threatens to disappear with every present, which does not recognize itself as meant in it.

To articulate what is past does not mean to recognize “how it really was.” It means to take control of a memory, as it flashes in a moment of danger. For historical materialism it is a question of holding fast to a picture of the past, just as if it had unexpectedly thrust itself, in a moment of danger, on the historical subject. The danger threatens the stock of tradition as much as its recipients. For both it is one and the same: handing itself over as the tool of the ruling classes. In every epoch, the attempt must be made to deliver tradition anew from the conformism which is on the point of overwhelming it. For the Messiah arrives not merely as the Redeemer; he also arrives as the vanquisher of the Anti-Christ. The only writer of history with the gift of setting alight the sparks of hope in the past, is the one who is convinced of this: that not even the dead will be safe from the enemy, if he is victorious. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.

Think of the darkness and the great cold In this valley, which resounds with misery. – Brecht, Threepenny Opera

Fustel de Coulanges recommended to the historian, that if he wished to reexperience an epoch, he should remove everything he knows about the later course of history from his head. There is no better way of characterizing the method with which historical materialism has broken. It is a procedure of empathy. Its origin is the heaviness at heart, the acedia, which despairs of mastering the genuine historical picture, which so fleetingly flashes by. The theologians of the Middle Ages considered it the primary cause of melancholy. Flaubert, who was acquainted with it, wrote: “ Peu de gens devineront combien il a fallu être triste pour ressusciter Carthage .” [Few people can guess how despondent one has to be in order to resuscitate Carthage.] The nature of this melancholy becomes clearer, once one asks the question, with whom does the historical writer of historicism actually empathize. The answer is irrefutably with the victor. Those who currently rule are however the heirs of all those who have ever been victorious. Empathy with the victors thus comes to benefit the current rulers every time. This says quite enough to the historical materialist. Whoever until this day emerges victorious, marches in the triumphal procession in which today’s rulers tread over those who are sprawled underfoot. The spoils are, as was ever the case, carried along in the triumphal procession. They are known as the cultural heritage. In the historical materialist they have to reckon with a distanced observer. For what he surveys as the cultural heritage is part and parcel of a lineage [ Abkunft : descent] which he cannot contemplate without horror. It owes its existence not only to the toil of the great geniuses, who created it, but also to the nameless drudgery of its contemporaries. There has never been a document of culture, which is not simultaneously one of barbarism. And just as it is itself not free from barbarism, neither is it free from the process of transmission, in which it falls from one set of hands into another. The historical materialist thus moves as far away from this as measurably possible. He regards it as his task to brush history against the grain.

The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the “emergency situation” in which we live is the rule. We must arrive at a concept of history which corresponds to this. Then it will become clear that the task before us is the introduction of a real state of emergency; and our position in the struggle against Fascism will thereby improve. Not the least reason that the latter has a chance is that its opponents, in the name of progress, greet it as a historical norm. – The astonishment that the things we are experiencing in the 20th century are “still” possible is by no means philosophical. It is not the beginning of knowledge, unless it would be the knowledge that the conception of history on which it rests is untenable.

My wing is ready to fly I would rather turn back For had I stayed mortal time I would have had little luck. – Gerhard Scholem, “Angelic Greetings”

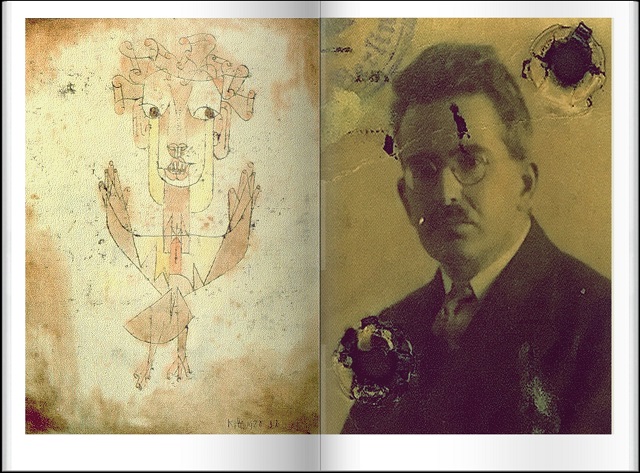

There is a painting by Klee called Angelus Novus. An angel is depicted there who looks as though he were about to distance himself from something which he is staring at. His eyes are opened wide, his mouth stands open and his wings are outstretched. The Angel of History must look just so. His face is turned towards the past. Where we see the appearance of a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it before his feet. He would like to pause for a moment so fair [ verweilen : a reference to Goethe’s Faust], to awaken the dead and to piece together what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise, it has caught itself up in his wings and is so strong that the Angel can no longer close them. The storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which his back is turned, while the rubble-heap before him grows sky-high. That which we call progress, is this storm.

The objects which the monastic rules assigned to monks for meditation had the task of making the world and its drives repugnant. The mode of thought which we pursue today comes from a similar determination. It has the intention, at a moment wherein the politicians in whom the opponents of Fascism had placed their hopes have been knocked supine, and have sealed their downfall by the betrayal of their own cause, of freeing the political child of the world from the nets in which they have ensnared it. The consideration starts from the assumption that the stubborn faith in progress of these politicians, their trust in their “mass basis” and finally their servile subordination into an uncontrollable apparatus have been three sides of the same thing. It seeks to give an idea of how dearly it will cost our accustomed concept of history, to avoid any complicity with that which these politicians continue to hold fast to.

The conformism which has dwelt within social democracy from the very beginning rests not merely on its political tactics, but also on its economic conceptions. It is a fundamental cause of the later collapse. There is nothing which has corrupted the German working-class so much as the opinion that they were swimming with the tide. Technical developments counted to them as the course of the stream, which they thought they were swimming in. From this, it was only a step to the illusion that the factory-labor set forth by the path of technological progress represented a political achievement. The old Protestant work ethic celebrated its resurrection among German workers in secularized form. The Gotha Program [dating from the 1875 Gotha Congress] already bore traces of this confusion. It defined labor as “the source of all wealth and all culture.” Suspecting the worst, Marx responded that human being, who owned no other property aside from his labor-power, “must be the slave of other human beings, who... have made themselves into property-owners.” Oblivious to this, the confusion only increased, and soon afterwards Josef Dietzgen announced: “Labor is the savior of modern times... In the... improvement... of labor... consists the wealth, which can now finally fulfill what no redeemer could hitherto achieve.” This vulgar-Marxist concept of what labor is, does not bother to ask the question of how its products affect workers, so long as these are no longer at their disposal. It wishes to perceive only the progression of the exploitation of nature, not the regression of society. It already bears the technocratic traces which would later be found in Fascism. Among these is a concept of nature which diverges in a worrisome manner from those in the socialist utopias of the Vormaerz period [pre-1848]. Labor, as it is henceforth conceived, is tantamount to the exploitation of nature, which is contrasted to the exploitation of the proletariat with naïve self-satisfaction. Compared to this positivistic conception, the fantasies which provided so much ammunition for the ridicule of Fourier exhibit a surprisingly healthy sensibility. According to Fourier, a beneficent division of social labor would have the following consequences: four moons would illuminate the night sky; ice would be removed from the polar cap; saltwater from the sea would no longer taste salty; and wild beasts would enter into the service of human beings. All this illustrates a labor which, far from exploiting nature, is instead capable of delivering creations whose possibility slumbers in her womb. To the corrupted concept of labor belongs, as its logical complement, that nature which, as Dietzgen put it, “is there gratis [for free].”

We need history, but we need it differently from the spoiled lazy-bones in the garden of knowledge. – Nietzsche, On the Use and Abuse of History for Life

The subject of historical cognition is the battling, oppressed class itself. In Marx it steps forwards as the final enslaved and avenging class, which carries out the work of emancipation in the name of generations of downtrodden to its conclusion. This consciousness, which for a short time made itself felt in the “Spartacus” [Spartacist splinter group, the forerunner to the German Communist Party], was objectionable to social democracy from the very beginning. In the course of three decades it succeeded in almost completely erasing the name of Blanqui, whose distant thunder [ Erzklang ] had made the preceding century tremble. It contented itself with assigning the working-class the role of the savior of future generations. It thereby severed the sinews of its greatest power. Through this schooling the class forgot its hate as much as its spirit of sacrifice. For both nourish themselves on the picture of enslaved forebears, not on the ideal of the emancipated heirs.

Yet every day our cause becomes clearer and the people more clever. – Josef Dietzgen, Social Democratic Philosophy

Social democratic theory, and still more the praxis, was determined by a concept of progress which did not hold to reality, but had a dogmatic claim. Progress, as it was painted in the minds of the social democrats, was once upon a time the progress of humanity itself (not only that of its abilities and knowledges). It was, secondly, something unending (something corresponding to an endless perfectibility of humanity). It counted, thirdly, as something essentially unstoppable (as something self-activating, pursuing a straight or spiral path). Each of these predicates is controversial, and critique could be applied to each of them. This latter must, however, when push comes to shove, go behind all these predicates and direct itself at what they all have in common. The concept of the progress of the human race in history is not to be separated from the concept of its progression through a homogenous and empty time. The critique of the concept of this progress must ground the basis of its critique on the concept of progress itself.

Origin is the goal [ Ziel : terminus]. – Karl Kraus, Worte in Versen I [Words in Verse]

History is the object of a construction whose place is formed not in homogenous and empty time, but in that which is fulfilled by the here-and-now [ Jetztzeit ]. For Robespierre, Roman antiquity was a past charged with the here-and-now, which he exploded out of the continuum of history. The French revolution thought of itself as a latter day Rome. It cited ancient Rome exactly the way fashion cites a past costume. Fashion has an eye for what is up-to-date, wherever it moves in the jungle [ Dickicht : maze, thicket] of what was. It is the tiger’s leap into that which has gone before. Only it takes place in an arena in which the ruling classes are in control. The same leap into the open sky of history is the dialectical one, as Marx conceptualized the revolution.

The consciousness of exploding the continuum of history is peculiar to the revolutionary classes in the moment of their action. The Great Revolution introduced a new calendar. The day on which the calendar started functioned as a historical time-lapse camera. And it is fundamentally the same day which, in the shape of holidays and memorials, always returns. The calendar does not therefore count time like clocks. They are monuments of a historical awareness, of which there has not seemed to be the slightest trace for a hundred years. Yet in the July Revolution an incident took place which did justice to this consciousness. During the evening of the first skirmishes, it turned out that the clock-towers were shot at independently and simultaneously in several places in Paris. An eyewitness who may have owed his inspiration to the rhyme wrote at that moment:

Qui le croirait! on dit, qu'irrités contre l'heure De nouveaux Josués au pied de chaque tour, Tiraient sur les cadrans pour arrêter le jour.

[Who would've thought! As though Angered by time’s way The new Joshuas Beneath each tower, they say Fired at the dials To stop the day.]

The historical materialist cannot do without the concept of a present which is not a transition, in which time originates and has come to a standstill. For this concept defines precisely the present in which he writes history for his person. Historicism depicts the “eternal” picture of the past; the historical materialist, an experience with it, which stands alone. He leaves it to others to give themselves to the whore called “Once upon a time” in the bordello of historicism. He remains master of his powers: man enough, to explode the continuum of history.

Historicism justifiably culminates in universal history. Nowhere does the materialist writing of history distance itself from it more clearly than in terms of method. The former has no theoretical armature. Its method is additive: it offers a mass of facts, in order to fill up a homogenous and empty time. The materialist writing of history for its part is based on a constructive principle. Thinking involves not only the movement of thoughts but also their zero-hour [ Stillstellung ]. Where thinking suddenly halts in a constellation overflowing with tensions, there it yields a shock to the same, through which it crystallizes as a monad. The historical materialist approaches a historical object solely and alone where he encounters it as a monad. In this structure he cognizes the sign of a messianic zero-hour [ Stillstellung ] of events, or put differently, a revolutionary chance in the struggle for the suppressed past. He perceives it, in order to explode a specific epoch out of the homogenous course of history; thus exploding a specific life out of the epoch, or a specific work out of the life-work. The net gain of this procedure consists of this: that the life-work is preserved and sublated in the work, the epoch in the life-work, and the entire course of history in the epoch. The nourishing fruit of what is historically conceptualized has time as its core, its precious but flavorless seed.

“In relation to the history of organic life on Earth,” notes a recent biologist, “the miserable fifty millennia of homo sapiens represents something like the last two seconds of a twenty-four hour day. The entire history of civilized humanity would, on this scale, take up only one fifth of the last second of the last hour.” The here-and-now, which as the model of messianic time summarizes the entire history of humanity into a monstrous abbreviation, coincides to a hair with the figure, which the history of humanity makes in the universe.

Historicism contents itself with establishing a causal nexus of various moments of history. But no state of affairs is, as a cause, already a historical one. It becomes this, posthumously, through eventualities which may be separated from it by millennia. The historian who starts from this, ceases to permit the consequences of eventualities to run through the fingers like the beads of a rosary. He records [ erfasst ] the constellation in which his own epoch comes into contact with that of an earlier one. He thereby establishes a concept of the present as that of the here-and-now, in which splinters of messianic time are shot through.

Surely the time of the soothsayers, who divined what lay hidden in the lap of the future, was experienced neither as homogenous nor as empty. Whoever keeps this in mind will perhaps have an idea of how past time was experienced as remembrance: namely, just the same way. It is well-known that the Jews were forbidden to look into the future. The Torah and the prayers instructed them, by contrast, in remembrance. This disenchanted those who fell prey to the future, who sought advice from the soothsayers. For that reason the future did not, however, turn into a homogenous and empty time for the Jews. For in it every second was the narrow gate, through which the Messiah could enter.

Walter Benjamin Archive

- Corrections

Walter Benjamin on the Philosophy of History (and the End of it)

How does Walter Benjamin use the insights of Marxism and theology to conceptualize history and the future?

What is history, and how will it end? These are the stark preoccupations of Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History. This article explores Benjamin’s attitude to history by tracing the structure of the theses as Benjamin sets them out. Given the intentional ambiguity and extensive quality of Benjamin’s argument, there is really no other way to approach it.

This article begins with Benjamin’s opening parable of the chess-playing puppet, before moving on to his analysis of human nature and class struggle. Benjamin’s critique of social democracy is explored, and the article concludes where Benjamin himself does – with an analysis of apocalypse and annihilation.

The Method of Walter Benjamin: What is Historical Materialism?

Given that it is one of the central concepts of the Theses , it is worth starting with a basic definition of what historical materialism is. It is the name given to Karl Marx’s theory of history, and it holds that the ultimate cause and moving power of historical events are to be found in the economic development of society and the social and political upheavals wrought by changes to the mode of production. It is the central concept Benjamin is attempting to analyze.

Benjamin begins with a story, apparently one he had been told rather than one he invented. In it, there is a puppet that appears to play chess autonomously. The chessboard is set on a glass table, which is shown to be empty. However, it only appears to be empty. This appearance is achieved by a system of mirrors. Inside, there is a ‘hunchback,’ who happens to be an expert chess player. The point of the analogy is this:

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

”The puppet called ‘historical materialism’ is to win all the time. It can easily be a match for anyone if it enlists the service of theology, which today, as we know, is wizened and has to keep out of sight.”

Historical materialism is the puppet, and theology is the hunchback.

Happiness and Redemption

The next section focuses on a quote from Hermann Lotze:

“One of the most remarkable characteristics of human nature is, alongside so much selfishness in specific instances, the freedom from envy which our present displays to towards the future.”

Happiness, Benjamin suggests, is bound up in our own time, or rather in reiterations and possible versions of our own time – friends we could have made, lovers we could have had, and so on. Benjamin goes on to suggest that “our image of happiness is indissolubly bound up with the image of redemption.” This, Benjamin says, can also be applied to the past. Every generation has a redemptive power with respect to those previous. “The past has a claim…which cannot be settled quickly”.

Conversely, one thing which reinforces the decision not to distinguish between ‘major’ and ‘minor’ historical events – that is, to not develop any sense of what is historically important – is to recognize that the criterion of historical importance is in the future: “only a redeemed mankind receives the fullness of its past.”

Class Struggle

Benjamin then moves on to attempt a novel definition of a central Marxist concept, that of class struggle. Benjamin defines it as the fight for the “crude and material things without which no refined and spiritual thing could exist.” The forms that the latter take in this context are certain traits or dispositions: “courage, humour, cunning and fortitude.” This is because they have retroactive force: they qualify all victories and defeats.

“As flowers turn toward the sun, by dint a secret heliotropism the past turns towards the sun rising in the sky of history.” Benjamin concludes with a warning about the subtlety of this change: “a historical materialist must be aware of this most inconspicuous of transformations.” Benjamin then returns to our conception of the past. He posits that the past can only be understood as a momentary image. He then quotes the writer Gottfried Keller: “the truth will not run away from us”, and claims that this is the critical move of historical materialism – the recognition of every image of the past in the present, without which the past threatens to disappear entirely.

Benjamin on the Messiah

On a similar point, Benjamin then goes on to characterize historical articulation as not a matter of recreating things as they really were, but as seizing hold of memory at a moment of danger. “The Messiah comes not only as the Redeemeer, but as the subduer of the Antichrist .” This is the image of the past which historical materialism is concerned with.

One of the recurrent themes in Benjamin is this sense of mission, of time which is not homogenous, but at once recurring and converging: “Only that historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins.”

Benjamin then turns to another element of recreating the past – that of empathy. This is, he claims, central to historicism – the attempt, among other things, to recreate the past. Here he quotes Flaubert: “Few will be able to guess how sad one must be to resuscitate Carthage.” The problem with empathy for Benjamin is that we shall generally end up empathizing with the victors. Another problem with the historicist desire to recreate the past is that it involves a veneration of cultural treasures, whose real meaning resides not just in the genius of those who created them but in the horror and barbarism of the conditions required to create them, which we are unwilling to contemplate.

The State of Emergency

The historical materialist disassociates himself from this standard way of viewing the past: it is “his task to brush history against the grain.” Benjamin is writing the theses in 1940, in the early days of the Second World War . It is striking that he first mentions fascism in order to emphasize how the state of things which has brought it about is anything but abnormal, and the apparent ‘state of emergency’ is not a genuine one. His call is for a real state of emergency, something to break with the past. We learn this, so he says, from the “tradition of the oppressed.”

This leads Benjamin on to, perhaps, the most famous passage in this work: that in which he describes the Angelus Novus (a painting by Paul Klee), taking it to represent the terrible bond history is held in: contemplating the horror of the past but forced into the future. The past is left behind, even as the ‘debris’ piles higher and higher. The storm which carries it, so Benjamin says, is called progress.

Benjamin then shifts direction, and characterizes himself and his project as one of turning away from the world and its affairs, imposing a kind of monastic discipline, or at least situating it as an extension of the tradition which counts monasticism as a part.

This turn to an ascetic life is necessary given the uselessness of politicians who are meant to be fighting fascism , their “stubborn faith in progress,” confidence in their “mass basis,” and “integration into an uncontrollable apparatus,” which Benjamin takes to be “3 aspects of the same thing.”

The point of this monastic ideal is to “convey an idea of the high price our accustomed thinking will have to pay for a conception of history which avoids any complicity with the thinking to which these politicians adhere.” Conformism within social democracy is a large part of its failure: Benjamin states that nothing has corrupted the German working class as much as the inertia with which it was going with the flow of history.

Defining progress in the context of technological development goes hand in hand with the centralization of labor as the source of power and wealth. It is Marx , Benjamin says, who notices the power dynamics which lie behind this shift in German society: “the man who possesses no property other than his labor power … must of necessity become the slave of other men who have made themselves the owners”. This conception of labor is paired with a predatory, consumptive view of nature. Benjamin draws the contrast here with Fourier’s utopianism, which focuses on unleashing the hidden potentialities in nature.

The Categories of Social Democracy

Social democracy assigns to the working class the role of redeeming future generations, rather than turning it into the last enslaved class fated to redeem generations of the past. According to Benjamin, progress in the social democratic conception involves the defense of dogmatic claims. In particular, (1) progress is of mankind itself, not just their “ability and knowledge;” (2) progress has no limit, in accord with the “infinite perfectibility” of mankind; and (3) progress was regarded as irresistible.

Criticism of progress should go beyond a critique of these dogmas of progress, and focus on what unites them; “the concept of the historical progress of mankind cannot be sundered from the concept of its progression through a homogenous, empty time.” History is not homogenous, because time is filled by the presence of now: “to Robespierre ancient Rome was a past charged with the time of the now which he blasted out of the continuum of history.”

Walter Benjamin on Revolution and the End of History

Revolution , for Benjamin, means introducing a new calendar. Awareness that they are about to “…make the continuum of history explode is characteristic of the revolutionary classes at the moment of their action.” The historicist gives the “eternal image of the past,” the “once upon a time” – the historical materialist must be able to conceive of the present not as a transition, but as time that has stopped entirely. This is the position from which history is written.

The historical materialist “remains in control of his powers, man enough to blast open the continuum of history.” Historicism logically concludes with universal history, whereas materialist historiography aims towards a “constructive principle.” Thinking is not just a flow of thought, but the point at which thought ceases, and the structure of that thought can crystallize into a monad. Benjamin concludes with the observation that this is a revolutionary opportunity to recapitulate the battles of history.

What Do Hegel and Marx Have in Common?

By Luke Dunne BA Philosophy & Theology Luke is a graduate of the University of Oxford's departments of Philosophy and Theology, his main interests include the history of philosophy, the metaphysics of mind, and social theory.

Frequently Read Together

Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project: What is Commodity Fetishism?

Walter Benjamin: Art, Technology and Distraction in the Modern Age

The Story of the Antichrist Pope

Theses on the Philosophy of History

by Pericles Lewis

Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress. [1]

In Benjamin’s interpretation of the painting, the angel is looking at us, the human beings who move through time. Much as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s modern Americans in their boats are ceaselessly borne into the past at the end of The Great Gatsby , Benjamin’s angel of history is irresistibly propelled into the future. History would be the attempt to make sense of the continual passage of time, but history is defeated by the same force that makes it impossible to fulfill all our dreams of what Fitzgerald calls an “orgastic future.” Time, progress, history—all are forces that constantly transform our lives and that we cannot halt or even adequately represent. [2]

- ↑ Walter Benjamin, Illuminations (New York: Knopf, 1969), pp. 257-8.

- ↑ This page has been adapted from Pericles Lewis’s Cambridge Introduction to Modernism (Cambridge UP, 2007), p. 32.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Guide to Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History”

Sean's Posts are a series of readers' guides that I wrote for my Spring 2017 Queer Theory and Posthumanism class at Westminster College. These guides were written specifically for this class and may contain allusions to other texts in the course, but they will also function as stand-alone guides.

Related Papers

Historical Materialism

Uwe Steiner’s Walter Benjamin: An Introduction to His Work and Thought is a comprehensive and compelling account of Walter Benjamin’s life and work, which will satisfy both newcomers to Benjamin and those with an existing interest. In this review, I argue that Steiner’s account goes beyond similar encounters with Benjamin in two main ways: first, by focusing specifically on Benjamin’s personal and intellectual relationship with ‘modernity’ and, second, by presenting Benjamin’s enduring appeal as a result of the creative interpretation of his work according to changing times and tastes. Yet Steiner’s historicising account of Benjamin also somewhat neutralises his critical potential as a historical-materialist thinker. Drawing on the work of Benjamin’s erstwhile friend and contemporary Ernst Bloch, as well as on Peter Osborne’s concept of modernity as a specific consciousness of time, I argue that the act of interpretation itself requires a weakly teleological concept of history, such...

David Jones

Matthew Charles

NOTE: This original entry from 2011 has been updated in a 2015 revision by the authors, available on the SEP website. Walter Benjamin's importance as a philosopher and critical theorist can be gauged by the diversity of his intellectual influence and the continuing productivity of his thought. Primarily regarded as a literary critic and essayist, the philosophical basis of Benjamin's writings is increasingly acknowledged. They were a decisive influence upon Theodor W. Adorno's conception of philosophy's actuality or adequacy to the present (Adorno 1931). In the 1930s, Benjamin's efforts to develop a politically oriented, materialist aesthetic theory proved an important stimulus for both the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory and the Marxist poet and dramatist Bertolt Brecht. The delayed appearance of Benjamin's collected writings has determined and sustained the Anglophone reception of his work. (A two-volume selection was published in German in 1955, with a full edition not appearing until 1972–89; English anthologies first appeared in 1968 and 1978; the four-volume Selected Writings, 1996–2003.) Originally received in the context of literary theory and aesthetics, the philosophical depth and cultural breadth of Benjamin's thought have only recently begun to be fully appreciated. Despite the voluminous size of the secondary literature that it has produced, his work remains a continuing source of productivity. An understanding of the intellectual context of his work has contributed to the recent philosophical revival of Early German Romanticism. His essay on ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technical Reproducibility’ remains a major theoretical text for film theory. One-Way Street and the work arising from his unfinished research on nineteenth century Paris (The Arcades Project), provide a theoretical stimulus for cultural theory and philosophical concepts of the modern. Benjamin's messianic understanding of history has been an enduring source of theoretical fascination and frustration for a diverse range of recent philosophical thinkers, including Jacques Derrida, Giorgio Agamben and, in a critical context, Jürgen Habermas. The ‘Critique of Violence’ and ‘On the Concept of History’ are important sources for Derrida's discussion of messianicity, which has been influential, along with Paul de Man's discussion of allegory, for the poststructuralist reception of Benjamin's writings. Aspects of Benjamin's thought have also been associated with the recent revival of political theology, although it is doubtful this reception is true to the tendencies of Benjamin's own political thought.

Karin Stoegner , Verlag Turia + Kant

Dennis Redmond

Original translation of Walter Benjamin's powerhouse essay on history, diachrony, synchrony and the utopian possibilities (and revanchist pitfalls) of historical change.

Chung Chin-Yi

Time is thus constellational rather than linear, where past events are teleologically linked with present events through an order which is redemptive and leading to an end which is redemptive and the arrest of all time with the Messiah " s return, who will judge the victors in history and bring victory to those who have been oppressed through class struggle throughout history, and this will entail bringing justice to the oppressed classes and judgement for the Antichrist as ruling powers from which even the dead will not be safe.Benjamin thus describes history as the procession and succession of a series of victors-these victors are the rulers in history, the political elites who have benefited from the spoils of capitalism and who have gained power from these spoils from oppressing the lower classes or working classes. History has always been shown to empathize with these victors in history, or the rulers or political elites who have derived their power from the oppression of the lower classes or proletariat. As Benjamin puts it, this empathy with the victors in history is also an occasion of horror because the spoils of victory owe themselves to the anonymous toil of contemporaries as much as their great minds and talents who have created them. Thus Benjamin holds that there is no document of civilization which is not free from barbarism, it is the violence of class oppression which has allowed the victors in history to maintain their power and advantage. The task of the historical materialist is thus to brush history up against the grain and also depict the losers in history who will be eventually redeemed by the coming of the Messiah who will bring justice for them and give them a voice. Only the Messiah himself consummates all history, in the sense that he alone redeems, completes, creates its relation to the Messianic. (Benjamin, 1978: 312)

Paula Schwebel , Andrew Benjamin

Zeynep Cansu Başeren

Rowan Tepper

Modernist Cultures

Keith Leslie Johnson

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

in The European Legacy: Toward New Paradigms 20.8 (2015).

Carlo Salzani

Walter Benjamin and History (Andrew Benjamin Ed.)

Philippe Simay

Astrolabio. Revista Internacional de Filosofía

Alfredo Lucero-Montaño

Journal of Modern Jewish Studies

Karin Stoegner

Book in Focus

Chris Cutrone

Proceedings from the Document Academy

Sabine Roux

International Political Sociology

Christian Garland

Journal of Speculative Philosophy

The Routledge Companion to the Frankfurt School

Martin Shuster

History and Theory

Richard T Eldridge

Darko Suvin

Laura Duhan-Kaplan

Walter Benjamin and the Subject of Historical Cognition,” in “Walter Benjamin Unbound,” Special Issue of Annals of Scholarship, Vol. 21.1/2, pp. 23-42

Sami Khatib

Jean-Michel Gouvard

Astrolabio, Revista Internacional de Filosofía

Marcos Antonio Norris

Sinkwan Cheng

A Contribution to the Author Meets Critics Session: Tyson Lewis's Walter Benjamin's Antifascist Education

Eduardo Duarte

Kipras Dubauskas

The Faculty Lounge of the Paris Institute of Critical Thinking

Alexei Procyshyn

Allan Megill

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Art

- History of Art

- Theory of Art

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Environmental History

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- History by Period

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Intellectual History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- Political History

- Regional and National History

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- Linguistics

- Browse content in Literature

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cultural Studies

- Browse content in Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Public International Law

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- History of Neuroscience

- Browse content in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Browse content in Economics

- Economic History

- Browse content in Education

- Higher and Further Education

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Political Economy

- Political Theory

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- Asian Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Native American Studies

- Browse content in Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Race and Ethnicity

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Reviews and Awards

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

Seminar Notes on Walter Benjamin’s “Theses on the Philosophy of History”

- Published: May 2016

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Appearing for the first time in English translation, this essay by the late Jacob Taubes demonstrates the lasting significance of Benjamin’s thought for understanding both historical and contemporary theological trends. Taubes’s translated notes provide some highly interesting insights into Taubes’s reading of Benjamin’s “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” and his interpretation of Benjamin in general. Because of the premature end of Taubes’s involvement in the seminar, the present notes cover only the first seven of Benjamin’s Theses in detail. Nonetheless, in the spirit of Taubes’s reading of the Theses, according to which “each one of [them] is a complete unified whole in which the entirety of the Theses can be found,” Taubes’s interpretation may be said to be incomplete and complete at the same time.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 7 |

| November 2022 | 3 |

| December 2022 | 4 |

| January 2023 | 8 |

| March 2023 | 3 |

| May 2023 | 8 |

| June 2023 | 5 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 6 |

| October 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 3 |

| March 2024 | 2 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- South of The Border

- Irish Times

- North African Dispatches

- Letters from Brussels

- Notes from the Margins

- Quebec Chronicles

- West Bank Diary

- Special Reports

- Photo Essays

- Olympics Watch

- Film & TV

- Music & Dance

- Short Stories

- Chess Corner

- Rob Murray's Monday Cartoons

- Weekend Comic

- Classical & Opera

- Hello Mozart

- Counterpoetics

- Unknown Spins

- Editor's Desk

- Modern Times

- Sabir on Security

- Diary of a Domestic Extremist

- Devil's Advocate

- CounterSpin

- Deserter's Songs

- The Unveiled Truth

- The Cutting Edge

- Passing for Normal

- On Corporate Power

- The Anti-Imperialist

- Shawerma Republic

- Beautiful Transgressions

- Radical Aesthetics

- Palestine is Still the Issue

- Reflections

- Sister Outsider

- Contours of Control

- Counter Narratives

- Under the Tree of Talking

- Secret State

- Africlimate

- Radar Reports

- Ghosts of History

- Ceasefire Bites

- Jody Mcintyre's Life on Wheels

- Paul Guest's Musical Notes

- The People in Between

- Ceasefire Shorts | Why BDS is working

- The Ceasefire Sessions

- The Rebellious Media Conference 2011

Walter Benjamin: Messianism and Revolution – Theses on History An A to Z of Theory

In theory , new in ceasefire - posted on friday, november 15, 2013 15:20 - 9 comments.

By Andy McLaverty-Robinson

“Benjamin sees Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus as depicting the Angel of History, looking back to the past.” (Source: 3.bp.blogspot.com )

Benjamin’s “On the Concept of History” , also known as “Theses on History” and “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, deals with the question of social transformation. This insightful short work is one of Benjamin’s best-known and most cited works. Of all his works, it develops Benjamin’s messianic ideas most completely.

The theses can be summarised as follows:

Thesis 1: Benjamin suggests that Marxism relates to theology much as an automaton relates to its operator. Despite its illusory determinism, Marxism is really articulating a theological response to capitalism-as-religion (see below).

Thesis 2: Every generation is endowed with a ‘weak messianic power’, because every past generation hoped for redemption or resurrection in the future. Benjamin implies that present revolutions ‘redeem’ or continue past revolutions – there is a line connecting them which is not that of linear time.

Thesis 3: Nothing is completely lost to history, but the past is comprehensible only from the position of redemption.

Thesis 4: The ‘spiritual’ is present in class struggle – even when it is about material things – as the drive towards redemption.

Thesis 5: The truth of the past is visible only as a tentative image which threatens to slip away. This image, presumably, is apparent in the continuity between past and present struggles.

Thesis 6: A revolutionary historian should not focus on ‘how it really was’, but rather, on seizing the image as it flashes by. This means one should seek to rescue ‘tradition’ from a ‘conformism’ which threatens to overwhelm it. The task is to set light to the sparks of hope in the past. On the other hand, the past is not safe from a victorious enemy. Today, images of the past threaten to disappear if the present does not recognise them.

Thesis 7: Current rulers are always the inheritors of the series of victories, and the guilt of past rulers. Every achievement of civilisation or culture is marred with barbarism, with the suffering of the exploited and excluded. The cycle cannot be broken by victory. This claim is based on Benjamin’s discussion of law as fate. The only way to escape such ongoing guilt is to ‘brush history against the grain’. This also means to be in continuity with the defeated of the past.

Thesis 8: The state of emergency is not an exceptional, but a normal situation (this idea is expanded by Agamben ). The rise of fascism requires the rejection of an idea of ongoing progress. Instead, revolution is directed against the current direction of history. The claims in theses 7 and 8 are critiques of the Marxian view of the ascension of humanity through progressive historical stages. As Benjamin argues elsewhere (in Central Park), Hell is not something to fear in the future, but is already present. The catastrophe is not around the corner if the system collapses. The catastrophe is the continuation of things as they are.

Thesis 9: Benjamin here analyses Klee’s painting Angelus Novus . This work of modern art is characteristically ambiguous, allowing the viewer to construct meanings from it. Benjamin sees it as depicting the Angel of History, looking back to the past. The Angel sees, not progress, but a growing pile of rubble. The Angel desires to redeem and put back together what is broken. But s/he is unable to do so because of a ‘storm blowing from Paradise’. This storm is what is called ‘progress’. In this analysis, Benjamin suggests a powerful image of history as an accumulation of ruins. He suggests that the power to resist this cumulative worsening is simultaneously ruptural and healing. Elsewhere he metaphorises it as pulling a stop-chord on a runaway train – the present system is a train with broken brakes, speeding towards disaster , and the messianic moment is like a stop-chord. In another passage, history is awakened with a slap born of long-contained frustration, not a kiss.

Thesis 10: Benjamin desires to make the current world and its drives repugnant, and critcises socialist politicians for their attachment to the goods of the present.

Thesis 11: Benjamin offers a critique of social-democracy for the idea of progress. The view of modernisation as progress is taken to ignore the effects of produced commodities on workers. It produces a corrosive conformity to the present, and lays the seeds for fascist technocracy. Here, Benjamin also contrasts the exploitation of nature to the release of its potentialities.

Thesis 12: Revolution avenges past generations. Progressivism reduces it to the salvation of future generations, and thus loses its ‘hate’ and its ‘spirit of sacrifice’ – which it needs.

Thesis 13: The idea of progress is inseparable from the idea of homogeneous empty time.

Thesis 14: The transformation of history does not occur in homogeneous empty time. It occurs in moments of immediacy ( jetztzeit ). It blasts particular moments of the present and past out of the linear sequence (and presumably the order of fate).

Thesis 15: Revolutions are necessarily experienced as rupturing the continuity of history.

Thesis 16: The present is not a transition between moments. Time originates and reaches a standstill in the experience of the present. Instead of an eternal past depicted as linear, we need a ruptural experience of particular moments which stand out. (This suggests an expressive relationship to temporal experience).

Thesis 17: The difference between progressivist and truly Marxist theories of history is that the former lists dates whereas the latter constructs time from a structure. The structure is based on the idea of a messianic zero-hour in which thought concentrates into a monad. This messianic moment explodes particular epochs, lives, or works out of linear history.

Thesis 18: Human existence is itself like a messianic zero-hour in the entire history of Earth.

Addendum A: Past events are given their historical meaning retrospectively, in messianic moments.

Addendum B: Awaiting redemption prevents time from becoming homogeneous and empty.

Analysis of the Theses

The most notable aspect of the theses is that they provide the clearest statement of Benjamin’s non-linear conception of time. Homogeneous empty time is associated specifically with capitalist effects on experiences of time. This is radical in its implications. Most everyday experiences of time are problematised as effects of capitalism. This is confirmed by studies suggesting that non-capitalist social groups experience time differently – as natural cycles rather than interchangeable instants, for example. Benjamin suggests that time would formerly be ‘filled’ by festivals and memorial days, creating connections between moments through time.

Homogeneous empty time is the kind of time measured by clocks and calendars. In homogeneous empty time, every moment of time is equivalent and empty. It is homogeneous because one “day” or “minute” or “hour” is treated as equivalent to any other. It is empty because, on the whole, it lacks special moments which give it meaning (in contrast to cyclical, ritual and biological time). It simply passes, and people fill it with contingent contents.

Homogeneous empty time passes in an eternal present which remains fundamentally the same. The new reproduces the old in a series of structurally similar moments. This experience of time arises from the constant replacement and renewal of commodities. People experience time this way because of its technological and social underpinnings in the capitalist way of life. In the Arcades Project, Benjamin associates homogeneous empty time with boredom.

The critique of homogeneous empty time has inspired authors studying phenomena such as nationalism and capitalism. Benedict Anderson’s ‘Imagined Communities’ shows the ways in which national identity, and modern cultural forms such as the novel and newspaper, depend on homogeneous empty time as an underpinning. E.P. Thompson shows how the imposition of homogeneous empty time was crucial to the creation of capitalist work-discipline when the working-class was first formed. Scholars working on global modernity often portray homogeneous empty time rubbing up against other, historically rooted ways of experiencing time.

Benjamin’s theory also resonates with Marx’s discussions of the importance of labour-time in commodity-production. Labour and commodities are only exchangeable because they can be treated as equivalent – and they can only be treated as equivalent because units of time are treated as identical. Commodity fetishism depends on homogeneous empty time. Homogeneous empty time is also associated with the closed world of fate and guilt.

Benjamin goes further than simply criticising capitalist forms of time. He suggests that excluded groups and revolutionaries can access another way of experiencing time, even in capitalist contexts. He suggests that the ‘messianic’ moment exists as a form of time.

This other kind of ‘messianic’ time is associated with the experience of immediacy, and the creation of non-linear connections with particular, past or future points. The present revolt is connected in spirit to past revolts. The present generation of activists is always potentially the messiah which past revolutionary movements were waiting for. If our own resistance ‘fails’ in the present, it may nevertheless be redeemed by some future movement, and is not in vain – unless the system wins so absolutely that the past is also ‘lost’.

Some similarities and differences can be listed as follows:

Homogeneous empty time is quantitative; messianic time is qualitative.

Homogeneous empty time is a continuous flow; messianic time is fully immediate.

Homogeneous empty time is experienced as anaesthetising, desensitising and meaningless. Messianic time is experienced as emotionally intense, like a drug high. It is filled or fulfilled .

Homogeneous empty time is continuous; messianic time is ruptural.

Homogeneous empty time is meaningless (empty); messianic time is the time of a ‘specific recognisability’ – it means something specific to those who experience it.

This view of time also suggests the possibility of ‘newness’ in history. The moment of messianic rupture – redemption or revolution – is also a moment when past debts and complicities are cancelled-out. This should be cross-read with the idea of law-destroying violence. By destroying the ability to enforce hierarchical exclusions and binaries, law-destroying violence ends the reign of fate. As expressive violence, law-destroying violence is ‘non-violent’, destroying the possibility of instrumental violence and therefore the ongoing complicities in past oppressions. This possibility is more radical than those considered by most poststructuralists.

In Esther Leslie’s reading, Benjamin sees messianic time filling the place left empty by capitalism. Capitalism sucks memory out of everyday life, leaving a space which messianic time can enter. Similarly, Gibbs argues hat messianic time unsticks the present from its seemingly necessary future. Instead, it establishes continuities with other, subterranean histories.

The revolutionary presence of now-time – jetztzeit – blasts open the linear continuum of history. In German, Benjamin contrasts jetztzeit or jetztsein – the present as ‘now’, as immediate – with erlebnis – the present experienced as if already past, as a moment in a process. This idea of immediacy is similar to that of Hakim Bey, and to accounts of the immanence of activist subjectivity, such as Peterson’s.

A revolutionary moment is a moment when messianic time enters and explodes homogeneous empty time. In such a moment, the whole of time is experienced as a monad. It is as if all life is reconciled and compressed into a single moment. The implication is that every singularity is brought into the new future, but minus the existing relations among different things. This moment is accessed through the dialectical image or profane illumination. ‘Truth’, in an expressive sense, appears in such moments. It causes things to leap out of their context.

The messianic moment also ruptures things from their particular locations in an order of things. Objects, ruins, ideas and language become rearticulable, or can be ‘redeemed’ (something Benjamin also relates to allegories, collecting, and non-standard uses). An old factory is ‘redeemed’ as a squat, a commodity is ‘redeemed’ as meaningful to a collector, a word is ‘redeemed’ by being used allegorically. A date such as Mayday, or November 17th in Greece, can capture a range of historical precedents and ‘redeem’ them in present revolt, ignoring the time-lapses inbetween.

The potential of allegory and montage is to seize upon the fragments of an experience which is already fragmenting, so as to create recognition or insight; the potential of collection is to rearrange objects in an esoteric world of their own. This removes the taint which the system (as order of things) otherwise places on objects, language and so on. Hence Benjamin is suggesting the possibility of a non-binarised, open-ended relationship to the world which occurs through praxis. This corresponds to the desire of the Angel of History to put back together the ruins left behind by history.

In writing, this “putting back together” occurs through the arrangement of references. For Benjamin, all texts are actually composites of different citations, or intertextual references. Every text is like a montage. In One-Way Street, Benjamin describes quotations in his work as akin to robbers, who leap out and rob the reader of her/his convictions.

In the article ‘Unpacking my Library’, Benjamin discusses the relationship of a collector to objects which are collected. Crucially, collecting is about liberating objects from their status as commodities or as instrumental objects for use. Instead, the collector places objects in a kind of magical arrangement. Collecting is thus a way of renewing the world. An object acquired for the collection is ‘reborn’ into it. The collector feels responsible towards the objects, rather than the reverse. Further, the collector comes to life in the objects. A collection exists between order (the arrangement of objects) and disorder (the passion for collecting). It is a passionate phenomenon. Collecting creates a mood of anticipation, and always carry memories from the moments of acquisition.

In One-Way Street, Benjamin re-enchants stamp-collecting via the idea of the postmark marking the face with weals or cleaving a continent like an earthquake. The collection of stamps can inventory places and dates in magical ways, and capture part of the power of great states.

In language, redemption occurs by way of allegory, or symbolic representation. Allegory overfills the present by filling it with a flash from the past. Allegories are akin to ruins. They are what is left when meaning or life is lost. It provides a vision of time and history which shows them in ruins. It also has a power to make anything mean anything else. Through allegory, the present is reconstituted as ‘expected’ – as the messianic moment which redeems the past. The way to make past phenomena present is to resituate them in the present space, connecting them to the present as a constellation.

In discussions of the poet Baudelaire, Benjamin celebrates the power of allegory. Allegory, according to Benjamin, stems from the gaze of an alienated viewer. It arises from flânerie . The flâneur stands at the margins of the bourgeois city. Intellectuals in particular were drawn into this stance by the precarity and uncertainty of their social position, creating the phenomenon known as ‘Bohemia’. Pre-Marxist revolutionary conspiracies emerged from the ‘rebellious pathos’ of this group, its ‘asocial’ stance. But flânerie is recuperated in the form of the department store. It was the means whereby intellectuals were ultimately brought into the market.

In the seventeenth century, allegory was the usual basis for the dialectical image – in this case, the perception of alienation. In the nineteenth century, when Baudelaire was writing, it was nouveauté (novelty). Nonconformists opposed the commercialisation of art and called for ‘art for art’s sake’ (perhaps seeking to preserve the aura of art). Benjamin sees this as a step backwards. The nonconformist as much as the commodifier ignored social phenomena. Ultimately, this view of art leads to epic delusions. Benjamin later connects this approach with the rise of fascism.

In relation to qabalah , Benjamin shares the idea that messianism can only be experienced outside the existing world. It requires us to turn away from the affairs of the world, as in a monastic withdrawal. But Benjamin’s withdrawal is more active. He is calling for the messianic moment to be experienced and used to transform the world.

Revolution is thus a kind of transubstantiation. A substance of one kind – commodities, homogeneous empty time, ordinary language – is transformed into another. It is the end of homogeneous empty time and of commodity fetishism.

It is also called ‘discovering the new anew’. Capitalism always presents us with the new, but the capitalist new is a return of the same. The new discovered anew is the possibility of radical novelty which is not a return of the same.

However, Benjamin is inconsistent regarding the extent to which messianism is realisable. In the ‘Theologico-Political Fragment’, Benjamin argues that the messianic moment consummates history, and is therefore necessarily incommensurable with it. The historical world therefore cannot be built on a divine or messianic model. It should be built on a model of happiness instead. This pursuit of happiness both contradicts and assists the messianic moment. Messianism is also the passing-away of the world. How can this be reconciled with the revolutionary role of messianism? It is possible that Benjamin saw messianism as a means of rupture between two ‘historical’ worlds, or that he simply changed his mind. I wonder, however, if the issue has more to do with how messianism can be used – in particular, an insistence that it must be lived in immediacy, and that politicians must not claim ‘divine’ authority for themselves.

The idea of ‘redemption’ in Benjamin’s work stems from his theory of messianism. Objects are redeemed by being used in alternative ways, distinct from their usual connections, and especially their exchange-values and their sign-values (e.g. as fashionable). This might be termed a bricolage or deconstruction of objects. Many examples can be found in the practices of squatters and other activists, in terms of the DIY reconstruction of everyday objects for new purposes – old stereos rescued from the roadside and reconfigured, scrap materials used in artworks and so on. One might think of this in terms of a ‘just in case’ rather than ‘just in time’ approach to objects, resonant with local knowledge and resilience rather than commodity systems.

Language is similarly transformed through allegory and translation. Technology also contains such potentials, revealed by children’s playful associations, designers’ fantasies and so on. Traditions of literature and theory can also be renewed through creative applications which are not confined to repetition.

Another important insight is the view that Hell or disaster is now . The theme of impending disaster is important both to reactionaries (the pending Hobbesian chaos if the system collapses) and to many progressives. Yet modernity already provides impending and ongoing disasters. Benjamin has in mind fascism and the First World War. Today we could also include nuclear weapons, ecological collapse, deaths due to capitalist enclosure in the South, the atrocities committed in the ‘war on terror’ and in many small wars worldwide, and maybe even 9/11.

It is common for such disasters to be portrayed as a violent eruption of an ‘outside’, which breaks into the otherwise peaceful development of (white, Northern) humanity. Benjamin reverses perspective, seeing such events as the Hell of the present. Benjamin seems to be seeing the ‘present’ in process here, so future disasters (World War 2 for Benjamin; today, such dangers as climate change, global war and increasingly dystopian regimes of social control) are extensions of the present, not threats to it. To stop these effects of the dominant system, it is necessary to put the brakes on it. Hope appears, not in what history brings, but in what arises in its ruins.

Benjamin here rejects the idea of progress as the extension or defence of elements of the existing situation. Instead, the messianic moment – Benjamin’s substitute for progress – is a radical interruption of the present. The messianic moment is in a sense radically exterior to the history it interrupts.

The idea of a permanent state of emergency is connected to this sense of ongoing disaster. Benjamin extends and criticises Carl Schmitt’s view, in which the state of emergency is the way the state (or ‘sovereign’) maintains its power in a context of contingency. Benjamin uses the idea of emergency to criticise, rather than reinforce, the social order.

There are both everyday and eruptive aspects to the implications of Benjamin’s critique. On an everyday level, Benjamin’s approach points towards activist practices of reappropriation of spaces and objects – squatting, DIY, bike repair, guerrilla gardening, home construction for projects such as pirate radio, and so on. He also implicitly endorses ‘subvertisement’, parody and other such symbolic means of disrupting established connections.

But he also seems to be calling for a moment of decisive rupture – a total insurrection, a Sorelian general strike, or a general movement of exodus. It is unclear how these two aspects of his project fit together. I would suggest that the messianic moment can occur firstly as an individual or small-group realisation, but that it can “redeem” the world only if it expands its scope.

Capitalism as Religion

The Theses on History provide a theological response to capitalism, because for Benjamin, capitalism is religious in nature. In ‘Capitalism as Religion’ , Benjamin argues that capitalism did not simply stem from Protestantism (as Weber argued), but is a religion in its own right. It developed parasitically by attaching itself to Christianity. Firstly, it reduces all of existence to its own standards of value. Secondly, it colonises all of time with this regime of value, as if every day were a day of worship. Thirdly, it is a cult based on guilt and blame (not repentance). It declares everyone to be guilty. It is a ‘cultic’ religion, of ritual practices, without ‘dogma’ or religious doctrine. Objects such as banknotes carry religious symbolism. It is an unusual religion because it offers not transformation but the destruction of existence. It flourishes on anxiety or ‘worries’, which ‘index the guilty conscience of hopelessness’.

Benjamin criticises Nietzsche and Freud for accepting what he takes to be aspects of the capitalist religion – Nietzsche because of the absence of a transubstantiation or messianic moment, Freud for reproducing capitalism in the unconscious. A rather literal activist equivalent of this reading of capitalism is offered by the performance activist Reverend Billy , who parodies traditional religious practices as means to protest against consumerism .

Andy McLaverty-Robinson is a political theorist and activist based in the UK. He is the co-author (with Athina Karatzogianni) of Power, Resistance and Conflict in the Contemporary World: Social Movements, Networks and Hierarchies (Routledge, 2009). He has recently published a series of books on Homi Bhabha . His 'In Theory' column appears every other Friday.

Perversion, fascination, habituation #2 « nuirs Dec 16, 2013 14:51

[…] Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920) and damaged portrait of Walter Benjamin (via Ceasefire) […]

Walter Benjamin: Messianism and Revolution – Theses on History | ΕΝΙΑΙΟ ΜΕΤΩΠΟ ΠΑΙΔΕΙΑΣ Jan 3, 2014 10:29

[…] https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/walter-benjamin-messianism-revolution-theses-history/ […]

Walter Benjamin: Politics of Everyday Life | Ceasefire Magazine Feb 18, 2014 19:51

[…] difficult to tie together. As a political writer, the implications of his work are clearest in his Theses on History and Critique of Violence. In the latter, he suggests that state power and ‘legal […]

Mark Jul 10, 2014 13:59